I fell in love with sorrow at a young age. I have been trying to understand why. Maybe it’s because my mom was always so sad—mostly in a hidden way, but it was there, moving beneath the surface of her skin, at the corners of her mouth and eyes, and there were a few times when I went looking for her and found her sprawled and cruciform on the floor, crying, pleading for help from a god who never came to save her—or maybe it’s because that’s how I taught myself to love myself. Because I was also always so sad. Or maybe, again, it’s because boys are taught that being men involves saving women and my fantasies were full of women (girls at that time) who suffered so that I could save them.

I could sense those who were sorrowful. This, too, is hard for me to understand. Was it a matter of “like knows like” or was it more predatory, the way I’ve seen serial abusers capable of almost immediately identifying those who were vulnerable, those who would never say anything when they were touched, no matter how much they disliked it? I have known many abusers like that. I have been touched by some of them. I think, more than knowing who was sad, often without us ever speaking, the question is what I did with that knowledge. How did I relate to, what did I do with, those whom I knew were sorrowing? Did I exploit their sorrow and my knowledge of it? Did I carry it gently? Did I impose? Was I a safe place? Looking back, it’s not always easy to determine the answer to these questions. They sound so mutually exclusive. Back then, they might have overlapped.

And here is another thing I have felt from a very young age: the desire to be comforted—fully, finally, once and for all, comforted. I think I found some comfort, a little, enough (sometimes, maybe), in comforting others. The question is if, in fact, what I thought I was offering as comfort was, in fact, experienced as comforting by others. Sometimes, I think it was. Sometimes, I think I was self-soothing at their expense while convincing myself that my actions were motivated by love for them. Other times, I think we were both doing that simultaneously. Maybe a lot of others times that was the case. Which is fine if that’s what you both know you’re doing—or at least it feels less cringey. It feels more like a beautiful nihilism, like the feeling you get when you start into your third beer and light your first cigarette because your stomach is finally settled enough to get drunk again, like the despair and defiance of a man who sets himself on fire, like fucking rock and roll. But it gets old after awhile. Eventually, self-soothing that way just makes you feel even lonelier and even sadder. Or at least that’s what it did to me. And so, even as I was pouring a little out for those who died before their time—in washrooms, on the concrete steps of the shelters that banned them, in medically-induced comas in the ICU, in holding cells at the cop-shop—I sometimes found myself envious of them.

(In all of this, I have learned to recognize these people as my companions: those who do not fear Death because we know, despite how much we desire to live, despite how much we love Life, despite how frequently we greet the sun with wonder, hold our uncovered faces up to the rain, or trail our fingers in the long grass, that only Death will be able to fully, finally, once and for all, comfort us and put an end to our sorrow. We may grieve those whom we leave behind [if we have anyone left to leave], we may grieve the lives we had or never had a chance to have, but parts of us, well, parts of us have been more than ready to go for a long time. For a very long time. For what feels like a lifetime.)

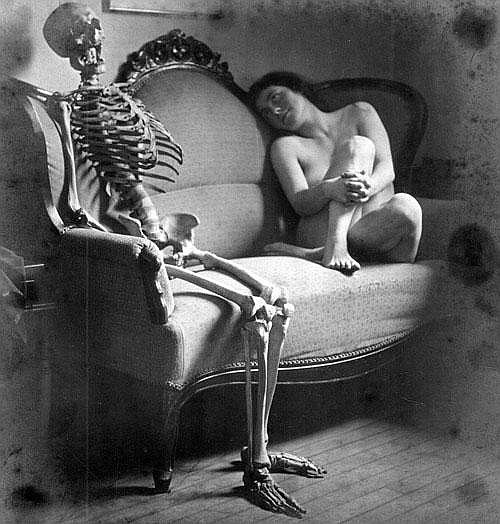

Ah, but those sad girls, how I loved them when I was young and untroubled by what romanticizing the suffering of women and girls said about me and men and boys and all the ways we go about doing us. How I longed to hold them and kiss their sad eyes. How I fantasized about their hurt and my taking it away. I dreamed about them inviting me to touch them. Of course, I would decline at first: “Are you sure this is what you want?” and they would say, “yes, yes, yes,” all breathlessly, as their hair fell in front of their face and their hands lifted my shirt and we embraced.

There must be a way to touch that heals. This, I think, is a belief that almost all of us hold, perhaps without being able to articulate it, from a very young age. Perhaps it is a residual memory from the womb. We know we can inherit trauma, fears, anxiety, and dependence on certain substances from the womb. So it makes sense, at least to me, to think that we also carry other formative experiences from that time when we were something else (blastocyte, embryo, zygote, fetus). It’s not just all the bad shit that gets passed on—good shit gets passed on, too. It’s important for people (especially people like me) to remember that.

And not only must there be a way to touch that heals, there also must be a way to touch that makes us know that who we are, just as we are, is fucking perfect, fucking glorious, fucking unhurt, untrammeled, unbowed and, even with our scars and limps and dreams that cause us to wake up screaming, unmarked. There must be a way to touch that calls forth our divinity. “Oh my god, oh my god,” we gasp, as we grasp and thrust and consume one another like the body and blood of Christ. And we are not wrong to say such things. But where boys (and then men) do go wrong is in thinking that this touch is theirs for the taking, as if they can touch and touch and touch, and take and take and take from girls (and then women). As if all these girls—hot girls, not girls, ladies whom men insist on calling girls, sad girls, party girls, conscious girls, unconscious girls, drunk girls behind dumpsters, homeless girls, best friend girls, study buddy girls, girls who need convincing, girls who don’t, girls who deserve it, girls who don’t but who should feel lucky to get it—only exist to the extent that they can resolve any and all of the desires, needs, fantasies, and sorrows of all the men they ever encounter. And this is often as true of “nice guys” as it is of frat boy rapists. The frat boys may define a woman as “a life support system for a pussy” but the nice guys, all too often, treat women as repositories of sorrow and even if women are full to overflowing, nice guys still find a way to slide a little more in, hot like a knife between the ribs. Or in the back. Or between the legs.

And me? I’m not valourizing sorrow any more. I’m not looking to save anyone—not even myself. My nights of self-soothing with the body of another, even as they self-soothe with mine, are over. And I’ve learned that beyond the binary of desolation and comfort, there is a third way—that of learning to be okay even in the most desolate of places and the most desolate of selves. Wholeness? Brokenness? What do we know of such things? What are they to me? I am both. I am neither. I am me. Here I am living the life where I finally learn, once and for all, that I’m okay.