1. Alcohol is Fun and You Can Still Be Responsible and Have Fun with It

With legal drugs (i.e., “controlled substances”) we understand that recreational, pleasure-inducing use is totally fine. In fact, such use for the sole sake of enjoying the feelings or affects induced by the drug is encouraged—not only by legal drug-producers and -pushers like the companies that craft, advertise, sell, or otherwise profit from people taking those drugs, but also by various drug-user cultures that are normalized within our society.

Thus, for example, all kinds of alcohol are marketed to all kinds of groups and various cultures arise in relation to various brands. If someone wants alcohol that comes from grain malt mash, or grapes, or distilled spirits, that says something about who they aspire to be. Working men drink cheap, patriotic beer. Wine moms drink wine. Hipsters drink IPAs. Rich men and boss women drink Scotch. People who hunt ducks drink Bourbon. I’m sure you can add other drug-use cultures to this list.

All of this occurs even though we are aware that these drugs can be dangerous and harmful. This is why they are controlled substances. Bars are supervised consumption sites for alcohol and they are widely available and easily accessible; businesses are required to ensure that they do not sell alcohol to those who are below the legal drinking age; people are legally forbidden from drunk-driving; alcohol products not intended for consumption aren’t sold alongside of Sherry, and so on.

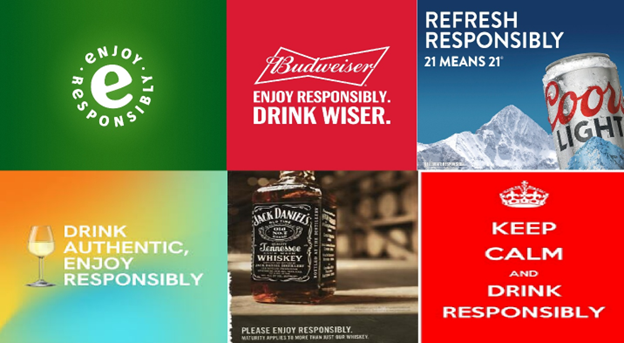

However, despite these various controls, harms still occur. Yet this does not lead to full criminalization or a total ban on the pleasurable use of these substances—such things have been tried in the past (the USA tried this with alcohol from 1920 to 1933), but these efforts always end disastrously and the harms caused by criminalization are vastly greater than the harms that persist when harm reduction is applied to alcohol and other substances and their use is both encouraged and regulated (countries like Switzerland and Portugal, as well as various studies done in Canada, Australia, the US, Germany, France, and a host of other countries demonstrate that this conclusion basically applies to all controlled substances that people also use recreationally). However, alcohol is the most widely available and taken-for-granted controlled substance. Therefore, because drinking alcohol can be a fun but not risk-free activity, the saying “enjoy responsibly” is ubiquitous in the drug-user culture associated with alcohol.

Observe: Nobody is saying that you shouldn’t drink for fun. They’re just saying that, when you do drink, you should try to do that in ways that don’t hurt yourself or others. Importantly, we’ve structured our society in such a way so as to institutionalize and legalize safer forms of controlled substance use (for this substance).

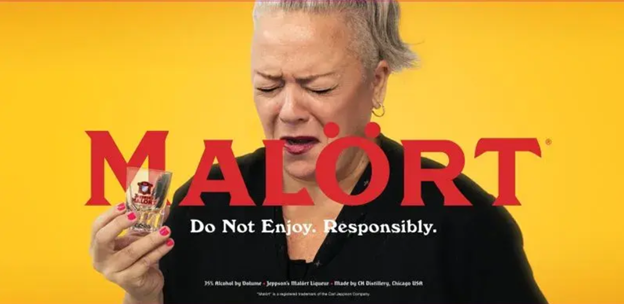

Read more: Enjoy! On “Not Obeying the Care”Drug users whose drug of choice is alcohol have a good deal of fun with this responsibility-oriented sloganeering. The Chicago-based company Malört plays with the observation that the bitters they produce actually taste, well, really fucking bitter and really fucking gross and so they created the following ad:

In fact, the whole injunction to drink “responsibly” is an easy target for all kinds of jokes (especially after you’ve had a drink or two!). Here are a few examples:

And this one makes me lol:

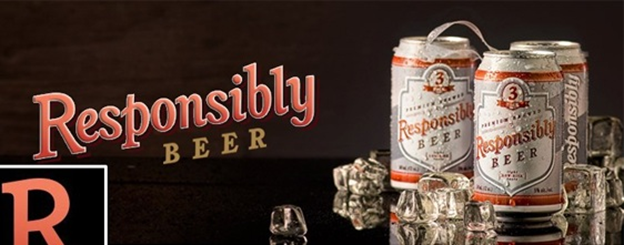

There is also a brand of beer “devised by [a] wacky entrepreneur” (according to the Daily Mail) that allows you to drink as much as you want while still drinking ResponsiblyTM:

You get the idea: (a) people drink for fun; (b) they are supported with this via harm reduction methods that have been tried and found to be far superior to criminalization; (c) and people who drink often laugh at the discourse that urges “responsible use” because, hey, sometimes people just want to get fucked-up; (d) and, hey, it’s okay to laugh at other people’s notions of “responsibility” (especially given the ways in which neoliberalism uses individual “responsibilization” as a way of depoliticizing our understanding of our context and as a club to bludgeon the oppressed); (e) and, hey, nobody is being treated like a shit-stain on the community just because they joke about how “drinking responsibly” means using a coaster and not spilling their drink; (f) and, hey, having kids is hard fucking work and if you want to get together with other moms and cry-laugh about how the only thing that sustains you is alcohol while sipping a glass of White Zinfandel, that doesn’t mean you’re a bad mom and you can totally do that.

2. Taking Medication is a Less Fun Way to Do Drugs but Sometimes Meds Really Help

In light of this, it’s interesting to observe how well-intentioned advocates of harm reduction, decriminalization, and care for people who purchase, possess, or use controlled substances in ways that have been criminalized, don’t talk too much about how using these drugs can also be a really fun experience (I include myself in this critical observation and what I say here relates to what I wrote in my recent post, What Do We Talk About When We Talk About “Addiction”?, so I won’t repeat here what I said there). This is because of the ways in which people whose possession or consumption of drugs has been criminalized are frequently portrayed as irresponsible, immoral, vice-ridden, lazy, ne’er-do-wells. Consequently, when talking about drugs, these advocates (again, myself included) tend to talk about drugs as medications.

For many people who have been forcibly impoverished, abandoned, oppressed, and pushed-out, access to healthcare simply does not exist in the same ways that it does for upper-middleclass members of dominant populations. It’s not hard for university students to get Adderall (which, as Carl Hart shows, is both chemically and experientially all-but-completely indistinguishable from crystal methamphetamine). It’s not hard for rich families to get Ritalin for their kids with ADHD. When you have money, it’s not hard to find doctors who take your pain seriously, who aren’t overly concerned about what you do with your pills (heck, you probably went to school with a number of other folks who became doctors and have them in your peer group), and who are willing to put up with you during appointments when you are ill-tempered, grumpy, “hangry,” or just acting like a White Man in PublicTM.

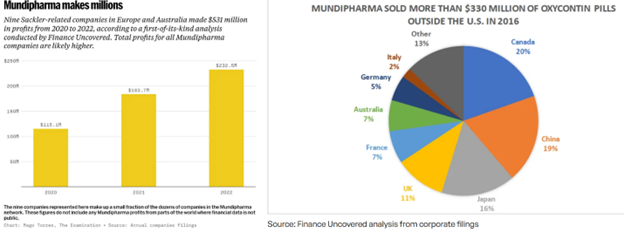

It also didn’t used to be hard for anyone to get opioids. Thanks to Purdue Pharma, the Sackler family, and tens of thousands of family doctors, a lot of low income folks, blue collar workers, and folks with various forms of temporary or chronic pain, could access opioids via their doctor or the Emergency Department at the local hospital. But the narrative shifted about opioids once it became clear that Oxycontin (remember Oxy80s? Heaven in a pill!) was very addictive and also rather more dangerous when it came to overdosing (Oxys, like the host of opioids that came before and after them, were first marketed as a low-risk, non-addictive alternative to other pain medications). So the regulators get more heavily involved and started threatening the doctors. The Sacklers were also dragged before the courts but they mostly got away with it and still have billions of dollars while amassing billions more—much of which comes from other companies they own outside of the USA selling both opioids and the drugs that are used to treat opioid addictions (and guess who holds the patent for Naloxone? Richard Sackler!).

Unfortunately (but not surprisingly, recalling that shit never flows upstream), going after doctors for “over-prescribing” just ended up producing a whole bunch of people who were physically and mentally reliant on opioids, often with chronic pain (and a higher sensitivity to pain due to regular opioid use—which was the drug-use schedule prescribed to them by their doctors) who could no longer access safe, pharmacy-grade medications. The very same doctors who created those chemical dependencies suddenly stopped providing the drugs.[1] As a result, people have needed to find alternative ways to medicate their pain, to address their withdrawal symptoms, and to try to and continue with wellness plans that, for many people, had worked just fine for years.

Knowing this, when people speak about “drug addicts,” or “people who use drugs,” or “substance abusers,” or “people who misuse substances,” advocates such as myself have been more inclined to replace all references to “drugs” and “substances” with the language of “meds” or “medications.” Hence, when it comes to the harms we associate with those drugs—like the mass number of deaths we associate with fentanyl and the so-called “opioid crisis”—comes down to having a safe supply—i.e., getting a guaranteed dosage of a guaranteed chemical cocktail from a reliable source (like a pharmacy) without any impurities mixed-in. Of course, a safe supply is what occurs when decriminalization occurs.

3. But Drugs Can Also Be Really Fun and That’s Great Too

Now, while I support this discourse, frequently employ it, and believe that it is an effective way to highlight biases that hide in plain sight based upon what we do and do not take for granted about different groups of people, I think it’s also important to emphasize that meds like opioids and other controlled substances can also be used recreationally and this is also totally fine! Sometimes the discourse of meds and its expansion into the domain of “illicit substance use” can end up being a form of respectability politics. Respectability politics, as Wikipedia handily summarizes it:

is a political strategy wherein members of a marginalized community will consciously abandon or punish controversial aspects of their cultural-political identity as a method of assimilating, achieving social mobility, and gaining the respect of the majority culture.

In this instance, the issue with respectability politics isn’t that it works to restore an inherent dignity and respect to certain drug users—that’s all well and good; rather, the issue is that this restorative work is done at the expense of other drug users, and is achieved by assimilating to oppressive cultural notions about what we are and are not allowed to do for fun, what the law is or is not allowed to tell us to do, and what it means to be responsible within a context where the notion of individual responsibility is commonly used as a tool for enforcing oppression. In fact, the picture below, while amusing (which is great—let’s be amused as we work through hard things, homies!), is also a very real presentation of one form of responsibility that applies to many people:

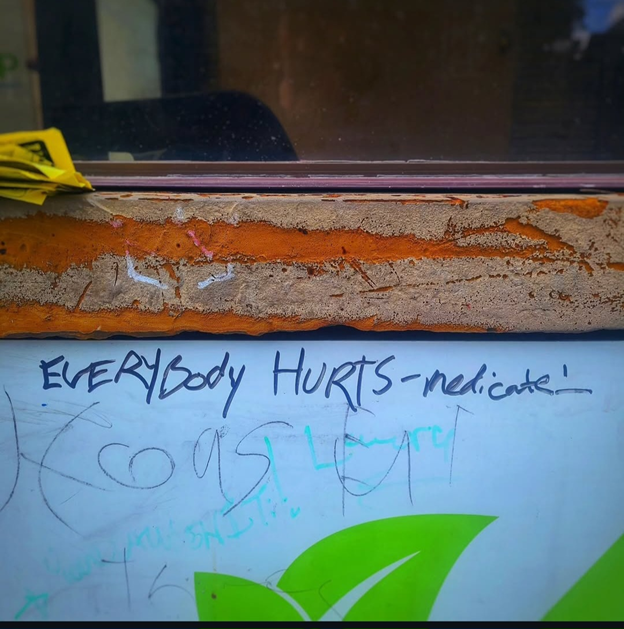

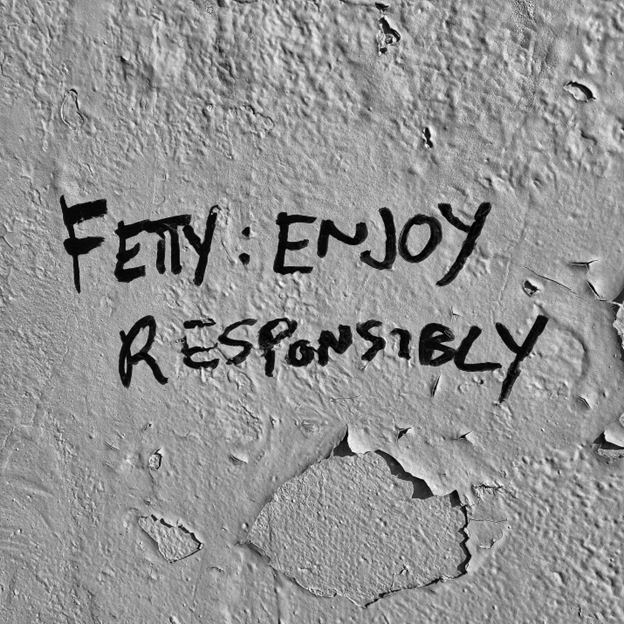

I was thinking about the joy of drugs and how advocates (like me) who talk about “meds” often inadvertently reinforce stigmas related to status quo values when I encountered the following piece of graffiti in a local stairwell (fetty = fentanyl):

Funny, right? But it also should make the passerby stop and wonder: “Hey, wait a minute, why do we take that stance with some substances that can be enjoyable-but-potentially-harmful but not others? Why do we draw the lines where we do? We do we take this slogan for granted when it comes to alcohol but not fentanyl?”

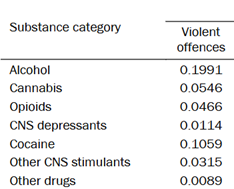

Well, large numbers of people are dying because they have accessed a toxic supply of fentanyl. As I have already argued here and elsewhere, this is because their access to this substance has been criminalized. However, the primary group of people who are fatally harmed by fetty-use are the fetty-users themselves. But, if we look again at alcohol-users, we cannot make the same argument. Not only are ~55% of fatal car accidents in Canada caused by impaired driving (with alcohol being the leading cause of impairment and recalling that the drunk driver is more likely to survive than others involved in the crash), but a 2021 report from Corrections Canada demonstrates that, of all drugs that people use, alcohol is the one that is most likely to be involved when violent crimes occur:

One could argue that the ubiquity of alcohol causes it to be over-represented here but: (a) we know that the harms it causes are less now that it is legal than when it was illegal; and (b) we don’t have to worry about something similar happening with opioids since a safe supply of fetty isn’t going to make you want to beat your spouse, crash your car into a family of four, or fight that annoying dude at the bar—it’s just gonna make you have one the best naps you’ve ever had in your life.[2]

Fetty, then, like a host of other drugs, is something that we should not stigmatize if it is used recreationally for the euphoria, relaxation, and sense of peace and well-being it offers (I mean, who doesn’t want to feel euphoric, relaxed, peaceful, and well?). However, because of the risks currently associated with its use (again, which are largely but not exclusively related to criminalization), the message to “enjoy responsibly” is an important one. By all means, enjoy the drug, but let’s try to be careful with it so that we do not harm ourselves or end up doing things we might regret because of how much we enjoy it (i.e., “do the drugs, don’t let the drugs do you”).

4. Unfortunately, It’s Hard to Enjoy Drugs When the Police Are Trying to Kill You for Doing Them

The problem, which should be apparent by now, is that criminalization, stigmatization, vilification, greed, cruelty, and the smug self-righteousness of those who are greedy and cruel, make it difficult for people to enjoy a lot of drugs responsibly. John Hardwick gets to the truth of this when he urges people not to do drugs because “if you do drugs you’ll go to prison, and drugs are really expensive in prison.”

In fact, we are currently witnessing a major assault upon people who enjoy drugs as supervised consumption sites across the province are being shut down and municipalities are shifting from talking about funding harm-reduction-based hubs to funding abstinence-based hubs (with many social services merrily going along with this in order to continue to lionize the funding). Due to this matter, and concerns about “open-air substance use,” massive increases to police budgets are being justified even though this means cutting other services to oppressed folx.

Thus, at the same time as safe, indoor spaces are being defunded and essentially banned via absurd regulatory strategies, the roaming gangs of cops in London (increasing from 2-4 officers to 6-8 officers with an embedded social worker from CMHATV) are becoming a much more regular presence on the street. This is a part of the law enforcement crackdown on “open air substance use.” Mostly, based on reports I have received from those who have nowhere safe to go in order to receive shelter, housing, and care, it sounds like the cops are telling people to “move along,” taking away their drugs, looking for reasons to detain them, and generally terrorizing them. The despair on the street right now is palpable.

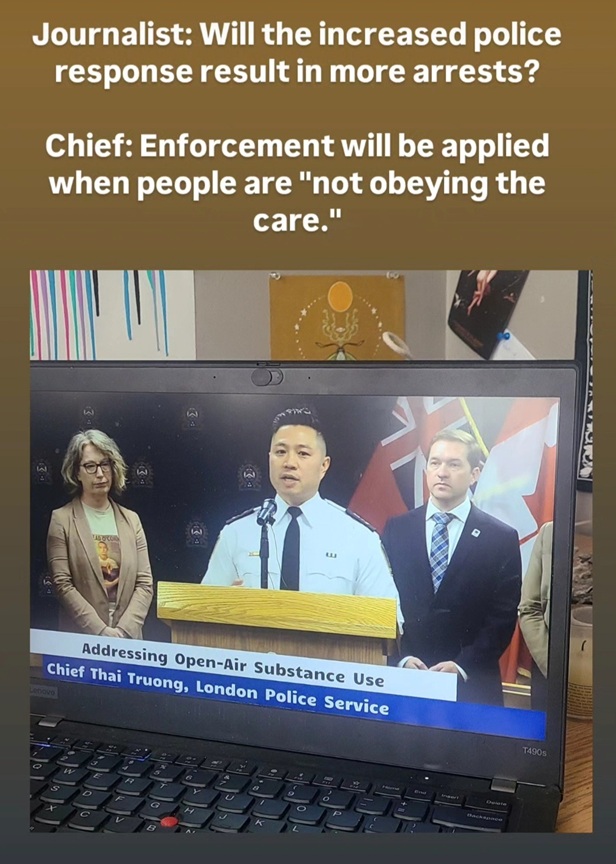

What’s remarkable is that all of this is being justified with the language of care. To be clear, it’s not remarkable that this language is being used—justifying oppression by calling it care has been around for ages (from White Saviours, to White Benevolence, to White Feminism, to White Social Working… wait, it’s almost as if there is a racialized and racializing element to oppression in our context…), and this tactic is alive and well today. What’s remarkable is that it still has any traction. People are still falling for this shit? That’s wild, because the ideology of care being administered by state-based violence workers leads to some truly outrageous and utterly laughable statements. For example, when asserting that increased policing is the solution to public drug use in our community, the chief of the local force had the following exchange with a journalist:

What a line! If you do not do as the police command you to do, you are “not obeying the care” and deserve to be punished with whatever amount of force the police deem necessary (I think even the chief, himself, realized the absurdity of his line which is why he kind of stuttered when he said it—he dove too deep into his own ideology and accidentally revealed how ridiculous it is)!

Thus, we can now add this line to a trifecta of fucking stupid things the police say when they brutalize community members:

And:

And then we can imagine the following:

That said, it’s also worth noting that we, as a community, feel compelled to do things like address “open-air substance use.” Why does it feel like “common sense” to all be talking about this? Why aren’t we looking at creating roaming gangs of cops and social workers to address “off-script Adderall-use at Western University,” or “cocaine-use in bars,” or “bowls full of every kind of drug imaginable at house parties in Old North”? If the police focused on any one of those areas, let alone all three, I’m absolutely certain they would bring in far greater amounts (both by weight and by dollar value) of drugs and I’m sure they would bring in higher level dealers. But the issue here really isn’t illicit drug use. It’s about helping the hoarders of (stolen) land and wealth move into neighbourhoods they deliberately impoverished so that those neighbourhoods can be gentrified, the already-impoverished folks can be forced to go elsewhere (“OBEY THE CARE!”), paying customers can move in and feel at home, and rich pricks can get a whole lot richer.

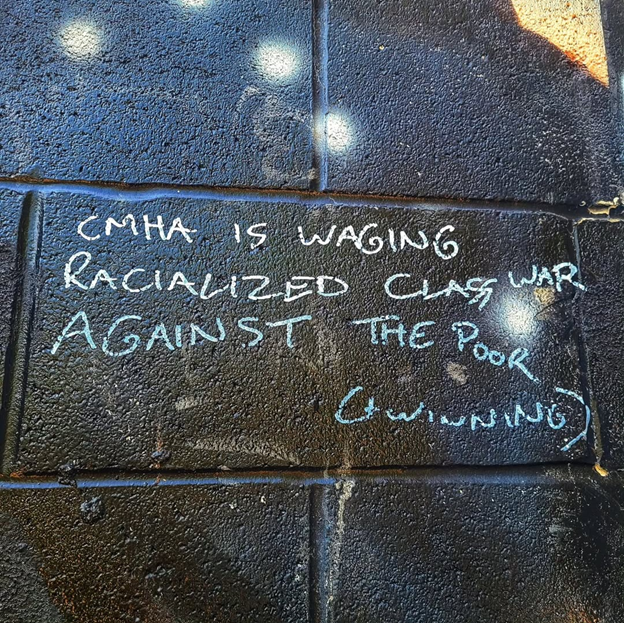

Therefore, when “care” looks like you getting your teeth kicked in by cops behind a dumpster because you were moving too slow while packing your things because you are in pain from withdrawing from meds you used to get from your doctor… when “care” looks like having to spend the weekend in cells and not being able to notify work and losing your job and then losing your housing because you couldn’t make rent, and then losing your kids because you lost your housing… when “care” looks like the outreach worker using their personal relationship with you as a form of “soft power” that enforces private property bylaws and moves you along (while the “hard power” of the police lingers in the background)… when “care” looks like not being able to receive medication for pain when you go into hospital with a spine infection that threatens your life, even though you have a considerable amount of pain but you’ve been flagged as a “pill chaser” and so you have to white-knuckle through the pain or self-discharge against the doctor’s orders… when “care” looks like being forced to go to places that are more and more removed from the general public and which afford a vulnerable person less and less safety and put you at greater risk for dying of an overdose from a toxic drug supply or being assaulted by a property owner who doesn’t want you in the woods by their house (homeless folks are assaulted by housed folks far more frequently than housed folks are assaulted by homeless folks)… well, it’s no wonder that graffiti like this is everywhere you look downtown:

I expect to see people saying more things about CMHA now that they’re part of foot patrol (CMHA already exploited the Black Lives Matter movement to launch their other police-CMHA collaborations and increase their funding—as a result, they currently have 15 executives on the Sunshine List [i.e., 15 executives earning more than $100K of public sector funding dollars]—but their presence on the street has been exceedingly minimal so they don’t get mentioned much by wall-writers) but the main thing one sees over and over, given that the primary organization that has been doing Bylaw Enforcement work for the City is called “London CARES” is the statement: “London Doesn’t Care.” This is just one playful variation on that theme:

Not surprisingly, when the carceral state and the discourse of health and care blur into a single entity (a process that has gone hand-in-hand with the secularization of so-called Western nations), people can respond by having a laugh at the norms that brand them as deviant, the policies and regulations that exclude them, and the laws that kill them. Instead of taking on shame or guilt for being branded as deviant or as a failure, one can embrace that identity, play with it, and be proud of it. Just like alcohol-users can laugh at the idea of “enjoying responsibly,” so also other-drug-users can celebrate their use.

This happens all the time in pop culture (Car Seat Headrest sings, “Drugs are better with friends are better with drugs” and it’s very easy to sing along!), and everyone loves a good-hearted outlaw (or even just a badass, “I did it my way” motherfucker) and, yes, there really is jouissance to be found in doing what some ding-dong authority figure tells you not to do—especially when all that ding-dong authority figure really CARES about is making the poor fuck-off so that the rich can get more rich.

So, look, if this is care then, hey, I’m not obeying the care and I’m having the best time doing that.

5. Taking Drugs from Homeless People is Soul Murder—So Smoke ‘Em If You Got ‘Em!

In light of the above, I find myself returning yet again to Henrik Ibsen’s observation that depriving another person of the ability to experience joy in life is “soul murder.” I think soul murder is a term that captures what happens when people with money and power force other people into a joyless existence, defined by serial abandonment, unrelenting pain, and total immiseration, and culminating in premature, preventable, grinding, and altogether shitty deaths. In Toronto, the average age of death for homeless men is 50—for homeless women the average age of death is 36. This isn’t just soul murder, it’s soul genocide.

It seems, when it comes to forcibly impoverished folx, three things are held to be true. First, they don’t own enough goods to be good people (Bylaw Enforcement officers make sure of this by constantly going around to people’s tents when they’re not home and throwing all their belongings into the trash—a regular, everyday, normalized and accepted form of robbing the poor to satisfy the rich). Second, they are not permitted to be in shared public spaces (you have to be a paying customer or, if you’re on the sidewalk, you have to be at least a potentially paying customer for the businesses that are nearby and you should never be present in such a way that you cause the slightest discomfort to other potential paying customers which, alas, simply being poor in public does). Third, the forcibly impoverished are absolutely forbidden to have any kind of fun at all. So they are vilified, pushed out of everywhere, told that this is all their fault, and not permitted to have any kind of fun or spend their tiny bit of money on anything but the bare necessities (which, it turns out, the tiny bit of money they receive from social assistance doesn’t cover adequately), and if they dare to enjoy themselves, engage in recreational activities, have fun, spend a weekend getting high in a hotel room with a locked door, a shower, and clean bedding, they are branded as the absolute worst kind of sinner “living a high risk lifestyle” and ultimately deserving the premature, preventable, grinding, and shitty death that comes for them. That’s soul murder, too, and it culminates in literal, physical, bodily death.

In One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, Omar El Akkad writes: “Forget pity. Forget the dead if you must, but at least fight against the theft of your soul.” He’s writing as an Egyptian-Canadian reckoning with the ongoing genocide in Palestine but I think his words also apply to the class war that is raging and escalating all around us everyday, across the globe and in the smallest local communities.

Getting high on fetty is a risky activity these days. It might kill you. But if enjoying that high and the pleasure it gives you is the only thing that is stopping the rich from stealing your soul—after they have already stolen your home and your land and your labour and your health and your children and your sense of belonging—then enjoy! And if you want to live, then try to enjoy “responsibly.” Try not to use alone. If possible, have Narcan and a sitter. If it’s available, use sterilized gear. Remember that smoking is a lot less risky than shooting (and, given all the deaths we’ve seen in the last few years, a lot of people have stopped shooting and only smoke now). And, with those things in mind, have the best time ever! You fucking deserve it.

[1] Although, N.B., as of 2023, there were still approximately 125,000,000 active opioid prescriptions dispensed in the USA. Similarly, in 2022 approximately 1 in 8 Canadians received an opioid script at some point. This highlights two important elements: (1) the class factor I have been addressing and the ease at which those who hoard (stolen) wealth are able to access these meds via the legally-mandated channels; and (2) the fact that only 10-20% of people who use any drug end up getting “addicted” (so way more people are taking opioids all the time and never getting “addicted” or ending up using them long-term).

[2] The legalization of cannabis is a good parallel here. Not that long ago, the government and the police were promoting the notion of “reefer madness” and, as they’ve done with innumerable other substances, arguing that smoking pot makes you sexually violent, monstrous, out-of-control, and so on (the FBI built itself up from a nothing organization into what it is today based on this). Of course, it’s all nonsense and the legalization of cannabis has not resulted in any spikes in violence or crime—in fact, as with the end of prohibition, it has created some real losses for organized crime.