Briefly discussed in this post: 14 books (Here Lies Bitterness; The Intersections of Whiteness; Colonial Desire; Learning From the Germans; Drug War Capitalism; The Unwritten Book; Young Mungo; The Wallcreeper; The Haunting of Hajji Hotak; Poppies of Iraq; Aurora Borealice; The Vagabond Valise; Stones Beneath the Surface; and Original Love); 2 movies (Moon Garden; and The Worst Person in the World); and 2 documentaries (Silver Dollar Road; and Camorra).

BOOKS

1. Fleury, Cynthia. Here Lies Bitterness: Healing from Resentment (2023 [2020]).

We may all feel resentment at times, Cynthia Fleury argues, but the pathway to wellness she presents is one where we learn to keep a critical distance from that resentment. It must be confronted and then buried, sublimated, so that something else can grow. In my readings, I have not encountered many who speak of the therapeutic benefits of sublimation. So I was curious to hear me—especially as I feel myself becoming embittered due to the ongoing obfuscations, denials, lies, complexifications, manipulations, and all-around death-dealing machinations of the civic bureaucrats I confront in my work. They help the rich get richer, the poor get poorer, and the poorest get dead (I have personally known more than 300 people deprived of shelter and housing who died premature and preventable deaths over the last 3 years). A massive number of good-hearted, committed, intelligent, and steadfast people have been working to try and change this in my context, but the civic bureaucrats are on the frontline of enforcing death-dealing neoliberal austerity and governance and they are smart (cruel people excel at being cruel in smart ways), well-funded (far more well-funded than us), well-staffed (far more well-staffed than those of us who have to find the time and energy to fight for change during non-paid hours), and they know they can fight and win an war of attrition against all of our efforts. They get six figure salaries and four to six weeks of vacation. We get starvation wages, work overtime so people don’t die (and then many of them still do die), have to also look after our families, have no benefits for therapy, have little time for organizing and working for real change (if we’re not collectively fighting with everything we have every single day, we are losing ground), and so we end up “burning out.” But, of course, this is a term coined and popularized by our abusers and oppressors. We’re not burning out. We being exploited, worked to death, gaslit, used up, and then discarded. Burning out? They’re blowing us the fuck up or putting us on a treadmill of meetings, committees, roundtables, conferences, and working groups, where we run faster and faster in order to go nowhere and when we collapse from exhaustion they say, well, I guess you weren’t doing enough self-care. So, yeah, maybe I’ve been feeling some resentment and bitterness about all of this unnecessary but inescapable death-dealing greed. Je m’excuse.

I thought reading Fleury’s book might give some insights into this topic, as I haven’t spent too much time thinking explicity about it. Quoting Max Scheler, Fleury argues that resentment is “the repeated experiencing and rumination of a particular emotional response reaction against someone else, which leads this emotion to sink more deeply and little by little to penetrate the very heart of the personality, while concomitantly abandoning the zone of action and expression.” Key here, in Fleury’s interpretation is the theme of rumination—wherein the feeling of being wronged in a specific way by a specific person is constantly fed, regenerated, and revived until it ends up expanding so that the resentful feels completely wronged in every way by everything, everywhere, all at once—and also the theme of inaction—wherein the resentful person feels like a powerless victim and, while there may be avenues to action available, the resentful person spends their time and energy feeding their feeling of powerlessness and victimhood instead of trying to work to change things. Thus, “the faculty of judgment henceforth puts itself in the service of maintaining resentment rather than deconstructing it.” In this way, an avenue to liberation becomes the means of maintaining “servitude and alienation.” Resentment embitters a person by foreclosing the possibility of escape. It becomes the fetish the replaces an unbearable reality. Key to this is the assertion that everything is the fault of others who must recognize their shortcomings but, as soon as the resentful person is confronted with their own shortcomings, they deny responsibility and present themselves as a pure and blameless victim of the shortcomings of others.

In order to avoid being devastated by embittered resentment, Fleury argues that one must develop something of a melancholic or stoic “taste for bitterness,” one that acknowledges resentment without giving in to it, one that sublimates the incurable, and one that knows when and how to give up on demands from justice from the outside world in order to do what one must do in order to heal oneself. According to Fleury, we must have:

the courage to no longer await reparations: not necessarily to forgive, but to turn away from the obsessive wait for reparations, the need to shut ourselves away within the need for reparations. Abandoning our grievance and even the justice of this grievance, taking this risk: not capitulating, but deciding that the wound will be somewhere other than in our mediocre exchanges with the other… Of course, reparation protocols, which are the product of institutions, are essential, even with all their short-comings. These protocols often constitute the central core of public police. But we’re speaking here of the individual: how he escapes his own resentment, how he extracts himself from social injustice, and also the prison formed by his own mental representations. Or how he finally comes to understand that one cannot repair that which was wounded, broken, humiliated: one repairs “elsewhere” and “otherwise”; that which is repaired does not yet exist.

Thus, in a stupefying process, resentment leads a person to close themselves off from the world from which they have concluded that cannot every expect to receive justice. Working around resentment means choosing to pursue Rilke’s notion of “the Open.” This is an approach to the world that sees it an free of imprisonment, the world experienced as “a yawning gap that is not a wound.” This means engaging actively in creativity and play. This means curiosity instead of rumination. This means recovering the admiration that resentment will eventually kill off in relation to everything, and discovering a renewed sense of wonder (admiration, according to Fleury, is defined as “astonishment before rare and extraordinary things, but it also implies the continuation of this astonishment” and resentment not only kills astonishment but actually ends of making a person hate more and more people and things all the time, while also increasing the enjoyment that person derives from feeling hatred). Critical to all of this is that a person constitutes themselves as an agent in their own life. One has the ability to change how one experiences the world. One has the ability to engage in the world in new ways. The world awaits.

That, then, is a rough summary of the first part of this book. The second part deals with fascism, particularly its contemporary manifestations, and how the upswelling of various White supremacist fascist movements relate to the politics of resentment. The third part engages with the topic of colonialism and also returns to Rilke’s notion of the Open and how this provides work around for those who have tasted bitterness and know, having once tasted it, that the taste lingers. All in all, I found this to be a fascinating, difficult, and challenging book. It provoked me, it challenged me, and it also changed me. There is no doubt that it has contributed to what I wrote in my recent blog post on the pursuit of madness).

2. Kindinger, Evangelia and Mark Schmitt (eds). The Intersections of Whiteness (2019).

Intersectionality was a term initially coined by a Black legal scholar, Kimberlé Crenshaw, to refer to the ways in which Black women are disproportionately harmed by the overlapping structures of racism (White supremacy) and sexism (the patriarchy). Since then, the concept has been expanded to look at the various intersections of power, privilege, oppression, and constructs of difference (prominent themes being race, class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, but themes related to ability, religion, cultural constructs of beauty, health, and wellness, caste, and species also frequently occur). This volume, edited by Evangelia Kindinger and Mark Schmitt, applies the concept of intersectionality to the overarching category of Whiteness. In this regard, it reminds me of the lyrics in Blood For Blood’s “White Trash Anthem”:

Your world is MTV. Spring breaks and ecstasy

You’ll get your hopes and you’ll get your dreams

Well, that choice wasn’t there for meMy world remains unseen (unseen by you)

Poverty, no family

Broken homes and broken dreams

I fall upon the thorns of life. I bleed…I ain’t your kinda white. I ain’t that kinda white

Never be your kinda white, I’ll never be your kind ’cause you made me

OutcastI ain’t your kinda white. I’ve never been your kinda white

I ain’t that kinda white ’cause I’m a lowlife outcast piece of white trash

Of course, there is nothing particularly new to a class-oriented exploration of the ways in which Whiteness was constructed in and propagated by wealthy Whites in order to make impoverished White identify with their oppressors and their oppressors’ interests (see also: the Tea Party in the so-called USA and the Freedom Convoy people in so-called Canada), instead of developing solidarity with impoverished BIPOC folks. The work of Theodore Allen, Nell Irvin Painter, and David Roediger all comes immediately to mind here. What the contributors to this volume attempt to do is to expand this race-class (or class-race) binary (and a lot of people do argue about which term should come first in that binary) to “elaborate on whiteness as a vehicle through which power is practised, not singularly, but multiply and heterogeneously.” Such studies are especially important at this historical moment because White supremacy, various forms of neo-fascism and ethno-nationalism, and “affective whiteness” are all resurgent (“affective whiteness” is what Matthew W. Hughey identifies as the “righteous anger” and “white victimhood” that have become the “dominant emotional ideals for performing a specific form of hegemonic whiteness” today—a theme that ties in very well with Cynthia Fleury’s study of resentment mentioned above). In this context, or rather, in various competing, contradicting, and overlapping contexts, “certain forms of whitness are being performed as hegemonic” and other forms of whiteness which “fail to exemplify dominant ideals” are marginalized. Hence, the authors argue an intersectional lens is required to understand how and why this plays out in different or similar ways in different contexts. This is why the authors speak of “white hegemony” (which is something always being negotiated, renegotiated, contested, tweaked, and reconfirmed) and not “white supremacy” (which implies a singular, supreme power). The contributors to the volume write primarily from the so-called USA, Britain, Germany, and South Africa. As with any collection of essays, I felt the final product to be a rather mixed bag, but I am grateful for the ways in which this volume encouraged me to continue to think critically, carefully, and creatively about these things. I think all White people have a moral imperative to learn about the history of Whiteness.

3. Young, Robert J. C. Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture & Race (1995).

Theories of race, Robert Young argues, are rooted in the (particularly British) colonizer’s uncertainty about himself, feelings of being estranged from himself and “sick with desire for the other.” It is driven by the colonizer’s desire to have a fixed identity in situations of conflict, instability, disruption, and change. Fears of fragmentation, pollution, dispersion, and disintegration arise in colonial and post-colonial contexts where the colonizer comes in close proximity to the colonized person he desires to both avoid and fuck (metaphorically and literally). From the 1840s onwards, “race science” or what we now refer to as a false or pseudoscience, was deeply concerned about this proximity, this nexus of conquest, colonialism, and desire, and it focused on the theme of hybridity and the production of degenerate “mongrels” (as when two different species have sex and are able to reproduce). Young uses much of this book to explore the history of that theory of hybridity as it developed and continues to influence contemporary discursive practices as they pertain to culture, race, and sexuality. I find Young’s earlier remarks about the already pre-existent hybridity, instability, and uncertainty of the colonizer’s identity (even pre-colonization as, for example, the British efforts to define themselves over against the Prussians demonstrates) to be particularly fascinating and wish he had spent more time here. However, equally fascinating and important is the time Young spends detailing how discarded theories pertaining to so-called race science and the notions of racial purity and theory carry on in anthropological and ethnographic studies of culture. Espeically when trying to track the essentialist roots of a culture or the purity of a culture before it was “contaminated” by contact (with the colonizer or the colonized). When this occurs, Young argues that cultural critics who are attempting to deconstruct colonial notions of race “may rather be repeating the past than distancing [themselves] from it or providing a critique of it.” I find this argument especially compelling in light of the works of Elizabeth Povinelli, Glen Coulthard, and Audra Simpson—all of whom have demonstrated how the cultural political of recognition have been designed in the courts of racial capitalism and settler colonialism to be used in a way that aids and abets the ongoing dispossession of the colonized. Young published this book in 1995 and I wasn’t sure how it would hold up now or if much of it would seem taken-for-granted in the realm of Indigenous studies but I found it to be a worthwhile read. Recommended.

4. Neiman, Susan. Learning From the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil (2020 2019]).

Susan Neiman is a White Jewish philosopher of German descent who grew up in the American South before moving to Berlin, then the Israeli occupation of Palestine, and then back to Berlin. The question that drives this book is what did Germany do in order to “work through” its past (in relation to the Nazis and the Jews) compared to what the United States has done (or not done) to work through its past in relationship to Black slavery (especially but not exclusively in the South as this pertains to the American civil war). Because, for the most part (Neiman argues), Germany has dealt well with its past, Germany is not seen as an anti-Semitic nation (although Germany’s rampant Islamophobia and the way this feeds into the ongoing Israeli genocide of Palestinians never merits more than two paragraphs in this entire book), but the United States is still very clearly a White Supremacist nation that has not worked through racial capitalism and anti-Black racism. According to Neiman, this has a lot to do with State-imposed responses, particularly in the domains of education and politics which took place in Germany but, if anything, have only regressed in the USA. Fundamental to the implementation of the German models (since both the East and West are examined, as well as the unified Germany after the fall of the Berlin wall), was the fact that younger Germans accepted the narrative the world told about Germany after the war and did not accept their parents’ assertions of innocence or victimhood. Americans have never faced this level of external compulsion (the USA has ever only been violently occupied by the American military and police, and not by invader armies or cops from other nations) and so stories of White victimhood and innocence persist at all levels and are still fundamental to American politics, economics, and law.

All in all, I found this book to be thoughtful and engaging. It introduced me to a number of organizations, projects and people involved in the struggle to make the world a better place. But I found Neiman to be rather optimistic about positive change. He outright refusal to speak to Israeli’s colonization of Palestine while exploring these themes was also, to deploy the moral language Neiman uses, inexcusable. What the heck.

5. Paley, Dawn. Drug War Capitalism (2014).

The central element of “drug war capitalism,” according to Dawn Paley, isn’t the drugs: it’s the capitalism. Given how regional, national, and international wars on drugs have done nothing to reduce the production, transmission, and consumption of drugs, it’s only natural to ask, well, what is being done with the millions of dollars that are being invested into these wars? Well, it turns out that the so-called war on drugs is a great way to seize common lands, steal territory from Indigenous nations, impose Western notions of private property, militarize society, terrify, dispossess, and disperse common folx, and bring racial capitalism and militarized statecraft to bear on territories and peoples that have previously eluded capture. In other words, this is less about drugs and more about the violent spread of neoliberal economics, law, and enforcement. Quel surprise!

6. Hunt, Samantha. The Unwritten Book: An Investigation (2022).

This book, a memoir mixed with literary reflections and Maggie Nelson-inspired autotheory, has one of the best beginnings I have read in awhile. It comes as no surprise to later learn that the narrator, who is also the author (but also not the author), later goes on to mention that they excel at (and delight in) writing the beginnings of stories. Alas, what begins as an almost Borgesian ghost-story goes sideways, in my opinion, with Hunt’s obviously very personal interest in the writings left behind by her recently deceased father. Long portions of the text are given over to these writings—writings Hunt acknowledges in the text may be of less interest to readers who did not have her father as their father—and the book suffers as a result. I was so excited after starting this book. But it did not live up to the expectation it created. A near miss.

7. Stuart, Douglas. Young Mungo (2022).

A Queer coming of age story set in the impoverished wasteland of inner-city Glasgow, I found myself thinking this book was a lot like a gay variation of the rape-revenge horror genre that I dislike so much. It’s like a gay, class-conscious literary version of I Spit on Your Grave. I understand that these fantasies can play a role in empowering people to militant self defense (as point made by Elsa Dorlin on her book on the subject), but all too often they feel like masturbatory fantasies that violent men get off on watching or directing (prime example: Gaspar Noé’s Irreversible). I don’t think Douglas Stuart was aiming for that… so what was he aiming for? I suspect a tragedy of Shakespearean proportions set in post-Thatcher Scotland (he tips his hand when he quotes Romeo and Juliet). Tragedy for the sake of tragedy is feeling a little played out to me these days. Plus, do the two pedophiles really have to be homeless men? Come on.

8. Zink, Nell. The Wallcreeper (2014).

The Wallcreeper is the kind of book you read and afterwards wonder, why does this book work so well as a book? This question prompted me to go and explore the reviews the book received and I found that, well, the critics were pretty evenly divided on if this book actually works at all as a book. It prompted strong feelings for and against it. Which is always an interesting thing. But, for me, the book works even though its structured in the kind of way that makes you think it wouldn’t or shouldn’t work. It drifts. It ties some things together. But not all things. The prominence of some themes remains consistent, follows a trajectory, that sort of thing, while other themes fall away. Which, you know, is kind of like life. And, I think, Nell Zink has created a book that feels alive with a person who feels like a person and not just a carefully crafted person-like protagonist. I very much enjoyed The Wallcreeper. Recommended reading. And if you end up not enjoying it, hey, it’s only a small book anyway.

9. Kochai, Jamil Jan. The Haunting of Hajji Hotak: And Other Stories (2022).

Jamil Jan Kochai is an Afghani who was born in a refugee camp in Pakistan and who came of age in the so-called United States of America. His short stories are brilliant, funny, poignant, and cut with a political edge. Thus, for example, he writes of an American kid playing Call of Duty (i.e. shooting Afghanis while playing an American soldier in a video game), who also takes advantage of the games tech to go and visit the village from which his family fled, while his traumatized and (to the teenager both annoying and guilt-inducing) Afghani father works in the garden. Definitely a distinct voice and far better than other stories about Afghanistan that have become best-sellers in American bookstores.

10. Findakly, Brigitte and Lewis Trondheim. Poppies of Iraq (2017).

The London Public Library does a massive annual book sale that has the very best prices for books in town. And the very best deals to be had at this book sale are in the graphic novels section. Literary graphic novels are usually relatively expensive (when compared to all-text books) and they also read much quicker than all-text books (given how the images are used to show the stories—more or less depending on the creators). So, it’s sometimes hard for me to buy a $45 book that I will probably finish in 2 hours. However! At the LPL booksale, I can purchase a literary graphic novel for a few dollars. It’s a helluva deal and, given the small number of graphic novels put out each year, it’s always the section I hit as soon as the sale opens. And that is why a number of graphic novels appear in my reading this month!

Poppies of Iraq, as with many literary graphic novels, is an autobiographical retelling and effort to make sense of the life lived by the author who, in this case, is a liberal Christian woman who immigrated to France from Iraq. As far as graphic novels go, it’s fairly word heavy, but, as with any heavily stigmatized part of the world where racial capitalism and Western imperialism have deployed the full spectrum of orientalist tropes (as per Said), it’s interesting to read more about the day-to-day life of the diversity of eeryday people who lived in Iraq pre-, during, and post-Saddam.

11. Steacy, Joan. Aurora Borealice (2019).

Literary graphic novels are really at their affective best when they engage with memoir, autobiography and, perhaps, autotheory. Aurora Borealis is Joan Steacy’s way of telling her story of growing up impoverished, being considered stupid because she had a learning disability that was never identified by the Ontario education system in the 1970s, and then how she ended up succeeding in the Toronto- and then Victoria-based art scene. Her lifelong curiosity and drive to learn no matter what systemic barriers she encounters along with her personal connections with the work and family of Marshall McLuhan(!), all make this an engaging work. Solid entertainment.

12. Siris. The Vagabond Valise (2017).

French folks have been doing comics and graphic novels for longer, with more art, and more creativity and intensity, than folks from a lot of other cultures. This is as true of French folks from France as it is of French folks from Québec. Siris writes and draws from this tradition and does an entertaining and also feeling-provoking job of telling the story of growing-up impoverished and in-and-out of foster care in Québec in the ‘60s and ‘70s. I found the story engaging and enjoyed the style (which reminded me a lot of Sylvia Rancourt’s Melodie series, as well as Craig Thompson’s early work, Goodbye, Chunky Rice).

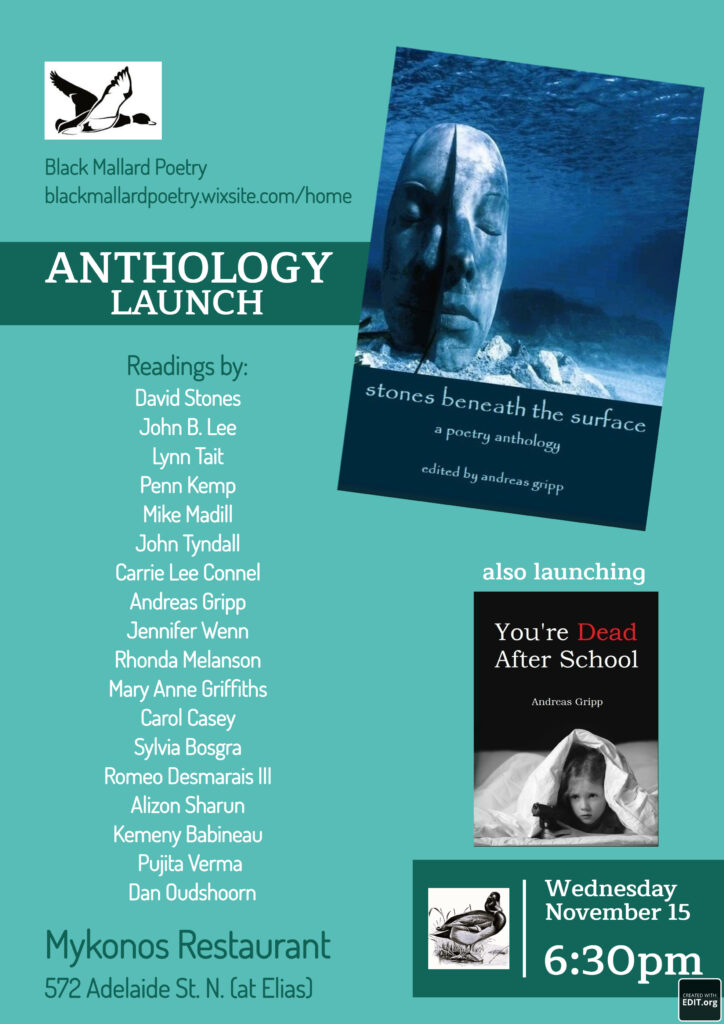

13. Gripp, Andreas (ed.). Stones Beneath the Surface: A Poetry Anthology (2023).

A solid and decently-sized collection of poems written by poets from so-called Southwestern Ontario (the region where I reside), the best thing about this collection is that two of my own poems are contained therein. They’re legitimately awesome poems. You should buy this book in order to read them. Seriously, you won’t regret it. I love my poems! Recommended reading for sure.

14. Peacock, Molly. Original Love: Poems (1995).

Dangit. It has been too long since I read this collection. I remember nothing about it. Did I enjoy it? Did I not? Was it decent? Did it leave me feeling nothing at all? Were there a few poems that grabbed me by the throat and kicked me in the heart? We’ll never know.

MOVIES

1. Harris, Ryan Stevens. Moon Garden (2022).

A stop motion animation about a gal who is on a quest to escape a nightmare realm? Sounds like my kind of horror-fantasy film! And it was… almost. I mean, I dig the creativity involved, I love this art form, and I’m on board for this plotline, but it just didn’t all come together and click for me. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoyed the movie. I liked it. I just didn’t love it. It did, however, introduce me to the best version of “Without You” that has ever been recorded (you can listen to it here).

2. Trier, Joachim. The Worst Person in the World (2021).

I wanted to like The Worst Person in the World more than I did. It started off well enough. The technique is there, the cinematography is on point, the acting is solid. Initially, I laughed a fair bit (a rare thing for me with movies!) but then, well, but then it never really goes anywhere. Well, things happen. We have a series of episodes that are related to each other and that each make a pedagogical point about the protagonist, I suppose, but I feel like it was a little too much “telling” and a little too little “showing.” It’s okay to want to make a point with art. Of course it is. Most artists are making some kind of point. But whether or not someone enjoys, appreciates, or is drawn in by an art piece has to do with how that artist goes about trying to make their point. Something feels off to me about how Trier goes about doing that with this film. But the obvious talent makes mes curious enough about his work to want to check out some of his other work.

DOCUMENTARIES

1. Peck, Raoul. Silver Dollar Road (2023).

I have watched and been strongly affected by several films Raoul Peck has directed (Lumumba [2000], I Am Not Your Negro [2016], Exterminate All the Brutes [2021], all come immediately to mind). So I was keen to see this film. It follows the Reels family which has owned a piece of waterfront land in North Carolina since slavery ended which wealthy Whites and real estate developers have been trying to steal for generations (and, although they have not quite succeeded yet, they have done a cracking job, as Peck demonstrates, of decimating the family along the way). It’s a quiet, grinding film documenting the war of attrition that people with endless funds are all too happy to play, as they deploy all kinds of technicalities, legalities, bureaucracies, and expert-fueled jargonalities, in order to further dispossess the already poor. In my opinion, it’s a striking illustration of the ways in which the globalization of neoliberalism and its forceful imposition on all peoples everywhere has become, to date, the most potent, powerful, and all-encompassing rule of law. Neoliberalism is not just an economic model, ideology, or praxis. It is, above everything, a way of structuring the law, of making that law absolutely all-encompassing, and of then enforcing that law. As such, neoliberalism also helps us to understand what the rule of law has always been about—the rule of the wealthy who are able to grow wealthier by ever, always further dispossession the poor. The rule of law is that which ensures the rich can grow ever richer while the poor grow ever poorer—because wealth qua wealth is created when some people are able to dispossess some other people, hoard that stolen wealth, and then use that wealth to dispossess even more people even more thoroughly. There is no wealth few without an impoverished many. This is what the law facilitates, naturalizes, valorizes, and moralizes. But we miss this because we’ve either bought into an ideology that is law-affirming and law-abiding or because the technicalities, minutiae, jargon, verbosity, and exhaustive rigour of legal codes either bores the fuck out of us (as it is designed to do) or utterly alienates us (again, as it is designed to do). This, I think, it fully on display in Silver Dollar Road. It’s a snapshot of one family’s experience but, I think, this family stands in for 90% of the world’s population. Recommended viewing.

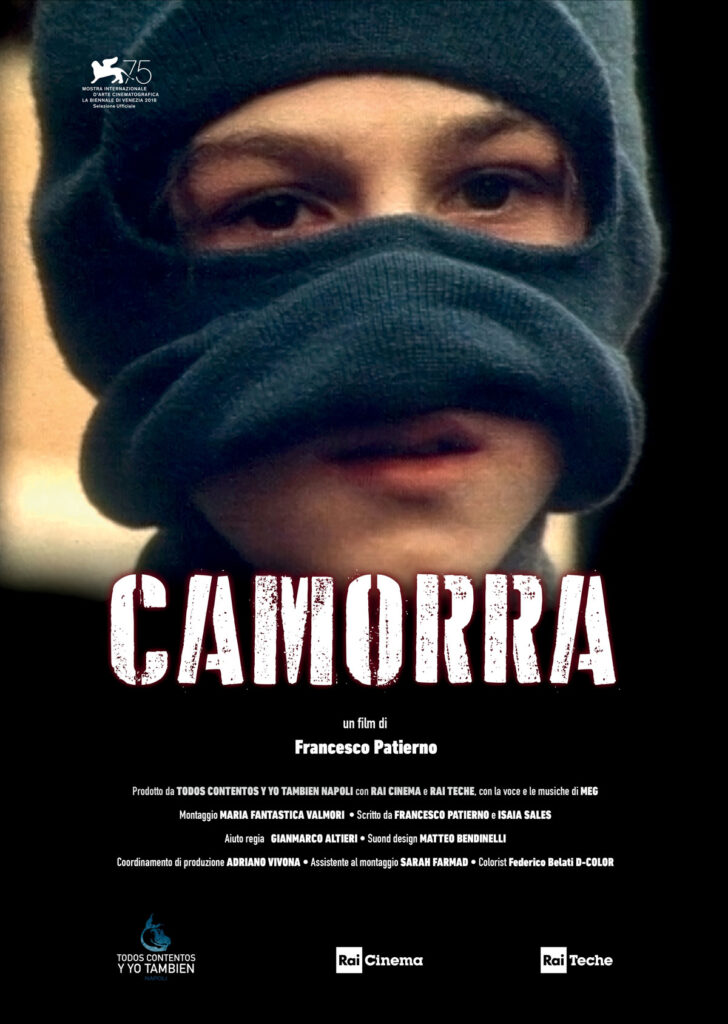

2. Patierno, Francesco. Camorra (2018).

Naples interests me because of Elana Ferrante. And Naples interests Ferrante for many reasons but, one that I find especially interesting is that way in which Ferrante distrusts, perhaps even despises Naples (although there is much she also loves about Naples) because of the ways in which the legal and illegal became inextricably mixed together in that city and how this mixing, in many ways, paves the way for the global hegemony of neoliberal legality (and illegality). In Naples in the 1980s, specifically in Campania, Ferrante sees something about the world that is to come—and she’s right.

The growth of the Camorra in Campania from the 1960s to the 1990s is the subject of this fascinating found footage documentary by Francesco Patierno. It shows how state-imposed poverty necessities survival by less-licit means, now the state must permit a certain amount of that less-licit activity in order to prevent a revolt against the systemic impoverishment the many, how this leads to the growth of a powerful criminal syndicate, and how this syndicate then blurs with the state. That’s the general drift and it’s a good one but the most compelling human-side of all of this are the interviews with impoverished women working streetcorners selling contraband cigarettes or with pre-teens in balaclavas who spoke of the robberies and murders in which they have participated. Ultimately, we see how greed combined with power brings about situations like this and so it is no surprise that situations like this abound under the current economic regime where the wealthiest 1% of humans own half the world’s wealth and the poorest 50% of humans own less than 1% of the world’s wealth.