Discussed in this post: 8 books (Pilgrim Bell; The Guiltless; Fictitious Capital; The Radiant Lives of Animals; Strictly Bipolar; The Hidden Spring; Shuggie Bain; and The Body Keeps the Score); 2 movies (Censor and Malignant) and 2 documentaries (The Rescue and Gunda).

Books

1. Akbar, Kaveh. Pilgrim Bell: Poems (2021).

I always experience some trepidation when I read new work by a poet whose previous work has resonated deeply with me. Poetry being as subjective as it is (or, at least, as I am about it!), means that I miss more than I hit when I read it and so when I hit, and hit hard, it’s a really rare and beautiful moment. Akbar’s Calling a Wolf a Wolf (2017) hit me hard and so I was both excited and nervous to read Pilgrim Bell. But it did not disappoint! I was deeply moved by the affective force of Akbar’s carefully-polished and oh-so-precise words. If you’re interested in seeing what is going on in the world of poetry, this isn’t a bad place to start. There’s a lot of beauty, tenderness, supplication, bravery, and world-weary-wisdom to be found here.

2. Broch, Hermann. The Guiltless (1950).

I am very interested in post-WWII German literature, especially as it pertains to masculinity, ethics, the rise of Nazism, and the question of guilt (see also Karl Jaspers and Klaus Theweleit). It is largely my understanding of what it means to be Canadian today that has brought me to this subject. We, too, are the authors of genocide. We, too, are bearing the fruits of an exceedingly toxic masculinity. We, too, feel like while that may be true of a few bad apples, it’s mostly not actually true of us. If Jaspers writes about the question of German guilty, then I have been interested in the question of Canadian guilt.

Broch’s contribution is an interesting one. He presents various character studies of people who would have viewed themselves as apolitical in the interwar period and during the initial rise of Hitler. His argument is that political indifference is also ethical indifference which then gives rise to “ethical perversity.” Mostly he seeks to show this rather than tell this, although I’m not convinced he entirely succeeds. That said, there are two quotations I want to mention, both of which I wish to connect to our contemporary context.

In our contemporary context, the public is increasingly aware of collective ways in which dominant populations have benefited from and continue to benefit from the oppression of others. Hence, critical race theory draws attention to systemic racism, decolonization reveals the structures of genocidal settler colonialism, gender studies reveal the violence of heteronormative patriarchy, and so on. Members of dominant populations, find themselves enmeshed with oppression but, unlike subaltern populations, they find themselves on the side of the oppressor. Hence, the first quotation from Broch that stood out to me: “our responsibility like our wickedness is always bigger than ourselves, and the deeper we have to plunge ourselves into our wickedness to find ourselves, the more responsibility we have to take for crimes we didn’t commit.” This is precisely what is required of Canadians who, for example, claim to be committed to a process of “truth of reconciliation” (and even more so the case for those who wish to pursue decolonization). We need to learn to take responsibility for crimes that we, personally and individually, did not commit.

The second quotation, however, points to the path Canadians are more likely to take. Flagrant celebrations of White supremacy, a doubling-down of Making Canada Great Again, the up-swelling of the new Klan in movements like PEGIDA or the Proud Boys, and the ubiquity of an overwhelmingly smarmy, self-righteous cynicism of Jordan Peterson fanboys all point to a refusal to face into the truth about our current situation. And this dies into the second quotation, which is Broch’s description of the Germans who end up contributing to the rise of Hitler (my comments in square brackets):

Humor comes hard to the German, and when he has it, it is a difficult, a twisted kind of humor, the humor of circumspect alternative [see all the Conservative dude-bros trolling online]. That is what characterizes his way of life and makes it so ponderous, a fluctuation between total asceticism [as with Proud Boys and their vow to not masturbate] and unrestrained eruptions of the instincts [as with all alt-Right outbursts of violence]. The German despises in-between solutions, he regards them as fraudulent, unaware that in taking this attitude he falls into a worse fraudulence… he, instead — and this is surely worse — misrepresents wrong as right by calling his unrestrained bestiality reason [as per the movement that coalesced around Trump], playing it off against the superior right of humanity, and so doing violence to right as such. His honesty is that of the violent man who in his determination to drive falsehood out of the world’s peace-loving swindlers [chants of “lock her up” in relation to Hillary Clinton come to mind], regards himself as a bringer of salvation and yet is inevitably a bringer of disaster because his doctrine is murder [see the exoneration of Kyle Rittenhouse].

Anyway, not the best book I have read on the subject, but this is a topic I think is well worth exploring together.

3. Durand, Cédric. Fictitious Capital: How Finance Is Appropriating Our Future (2017).

In my ongoing attempt to understand why we all feel stuck within a certain kind of world, even though we know that this world sucks for most people and even though good-hearted and intelligent people are trying to make it otherwise, I’ve been trying to understand shifts that occurred within capitalism in the last 20-40 years (since the advent of neoliberalism and the internet and the ways in which both have fostered a novel and very powerful global juridico-economic system). Finance capitalism is very different than industrial capitalism–money starts growing from money through what are essentially down payments on anticipated future profits and through all kinds of tools designed to grow money from money rather than, say, through heavy investments into various means of production. Financialization, via highly developed technologies and global capital flows creates an entirely different world for rich people to become richer, than what existed even half a century ago. Understanding this helps us to understand why analyses and alternative paths forward that are created based on what we understood about economics and politics up until the 1980s or even the 2000s don’t end up getting us where we want to go. So, I appreciated Durand’s book. It helped introduce me to numerous concepts, tools, and practices that are operative in the realm of finance and how they go about accelerating the ways in which the wealthiest 1% can increasingly dispossess, plunder, make superfluous, and leave for dead the other 99% of us.

4. Hogan, Linda. The Radiant Lives of Animals (2020).

Robin Wall Kimmerer has shown all of us the astounding wisdom and beauty that can arise at the nexus of literature, Indigenous ways of knowing, and more Euro-centric forms of plant science. Both Gathering Moss (2003) and Braiding Sweetgrass (2013) are outstanding. So when I heard that Chickasaw poet and elder Linda Hogan had written something that was, perhaps, similar to Kimmerer’s work, I was keen to check it out (side note: this is not the Linda Hogan who was married to Hulk Hogan; this is the other Linda Hogan). I wasn’t terribly moved by it. The best passages were the poems which made me want to read more of Hogan’s poetry and less of her prose. Onwards then.

5. Leader, Darian. Strictly Bipolar (2013).

Darian Leader, rapidly becoming one of my favourite authors writing in the psy-disciplines. In this work, he examines how a diagnosis that once applied to less than 1% of the American population has not exploded to be applied to roughly 25% of Americans. The prescription of bipolar medications to children has increased 400% since the mid-1990s and the overall diagnosis of bipolar has increased 4000% in the same time frame. Leader observes the mid-1990s was when the patents expired on the biggest-selling antidepressants and so alternative diagnoses (between 20-35% of those diagnosed with depression in primary care how their diagnosis switched to bipolar) allowed for alternative drug markets (sodium valproate [Depakote] was patented just as the major antidepressants were losing their patents). At the same time, the definition of bipolar itself was massively expanded (I believe there are currently five main types of bipolar recognized by the DSM-5, one of which is cyclothemia which is basically experiencing “noticeable” emotional ups and downs but not ups and downs that are as “extreme” of those found in other kinds of bipolar… so, like, basically being alive). This happened, in part, because psychiatry has increasingly moved to a symptomological approach to mental health and illness. Bipolar disorder, then, is a aggregate of symptoms which can be taken apart and treated individually so that we all find the specific cocktail that treats these symptoms (symptoms which, in turn, are increasingly treated as related to genetics rather than life history or context within mainstream psychiatry).

Observing all this doesn’t mean that Leader thinks bipolar doesn’t exist. Leader very much believes in bipolar disorder—he just thinks it’s something more and something different than simply having high and low moods. Rather, bipolar has to do with the quality of those highs and lows, the relation between them, and the thought processes underlying them.

Beginning with mania, Leader observes that bipolar mania as some key motifs: the sense of connectedness with others and the world, spending money people don’t have to spend, having a large appetite for food/sex/words/whatever, reinventing one’s self, verbal dexterity and newfound wit, and a movement towards paranoia. Of these, Leader emphasises the sense of connection with other people and the world. This sense of connection gives rise to a desire to communicate with others (something that distinguishes true mania for other states of elation and also from other forms of psychosis wherein people are happy to communicate with other voices or listeners that the rest of us cannot see). Thus, manic people like to talk a lot, and they need other people to talk to or at. This, then, links into the reckless promiscuity observed in many who are bipolar and manic—sex, too, is a form of communication (not just intercourse, as Leader observes, but discourse). Fidgeting, too, comes about because of the pressure to speak and keep on speaking. What Leader observes is that this form of mania tends to arise in people who experienced a fragile sense of connectedness or an “excruciatingly discontinuous” sense of connection when they were children. Hence, Leader remarks, it is not surprising to see bipolar passed down through generations as the experience of a parent’s or grandparent’s mania and depression crystalizes this experience of the world and others in the child (in other words, this may have more to do with complex epigenetics and which genes get turned off and on based on life experiences and the life experiences of our immediate ancestors, rather than with genetics qua genetics as per mainstream psychiatry).

Leader finds childhood experiences amongst bipolar people who exhibit grandiose fantasies about themselves as they reinvent themselves (or become someone else entirely) when they are manic. All too often, Leader argues, these people are children from families where the parents were striving and making great sacrifices to improve the socioeconomic status of the family and having great hope that their child will succeed in ways that were never possible to them. The child is then forced to try and meet an impossibly high standard. This, then, also explains why success (and not just failure) can trigger mania. Reaching the goal proves unsatisfying (because the goal met was also the desire of the Other not of the self—“Desire full stop is always desire of the Other” as Lacan observed). Mania follows after.

What then of the spending sprees that all-too-often accompany mania? Instead of viewing them as narcissistic, Leader correctly observes that they usually motivated by a sacrificial altruism—tipping a cab driver thousands of dollars, giving away all of one’s belongings as a part of a “Love Revolution,” and so on. Here, Leader suggests, that bipolar person may be driven to try and rid themselves of a feeling of indebtedness that they have—not only because of what they have or have not done, but also debt they have inherited from their parents or grandparents. Guilt that is not assuaged, after all, is passed on to each next generation and crystalizes neither as paranoia (the Other is to blame) nor melancholia (it’s all my fault), but as a back-and-forth see-sawing between highs and lows (because the responsibility that departs during mania comes back with brutal force and weight during the depression that follows).

Not only this, but this sacrificial altruism also belies the need of the bipolar person to maintain a belief in a good Other and a kind and generous world. Thus, just as the bipolar person experiences a sharp divide between mania and depression, so also in their mania they try to live entirely in the presence of all that is good and keep away from all that is bad. This then forecloses their feelings of guilt. Not only this—it can also be a way of avoiding one’s one feelings of rage or one’s desire to cause harm to others. As Leader writes it: “Rather than grappling with the messy, turbulent mixture of love and hate, destruction and admiration, the manic-depressive person opts for a more extreme and ultimately more coherent solution: to separate love and hate categorically.” This helps to explain why intense anger can also be something that initiates a manic episode. At it’s core, then, Leader argues that bipolar is not about fluctuating moods but about trying to separate and purify the extremes of good and bad, love and hate.

This, too, is why bipolar people may be more inclined to seek out or create an idealized Other who is an unimpeachable authority (versus schizophrenic people who are more inclined to question authority). Because mania forecloses debt, debt that is related to a very problematical intermixture of good and bad (often in parents or other caregivers and their relationships with the bipolar subject), a new debt is created to a consistently benevolent authority figure.

Yet, as the high of mania recedes, hatred re-emerges, often through a paranoid focus on a particular person or group. The re-emerging badness that contaminates the purity of the world of goodness and love experienced in mania, is projected onto this Other subject in order to try and prevent the intrusion of the mixed-up contaminated world (which brings the depths of depression with it). Thus, whereas in melancholia when the depressed person blames themselves entirely for all that is wrong with them or the world, in bipolar depression the subject oscillates between blaming self and blaming others (often with violent revenge fantasies attached). This then can give rise to the overwhelming exhausting and chronic fatigue often experience by bipolar people at their lows.

But what about when mania and depression come and go seemingly at random? The cycles aren’t random at all. Leader argues (and fits well with trauma research on this point) that episodes tend to occur on anniversaries of significant events—even if the person has no memory of those events. “The appeared precisely because the memory didn’t.” Not just on anniversaries, episodes also occur at moments when “an unintegratable element appears in that person’s life, such as the rage towards a loved one that cannot be easily processed or a reminder of a guilt that has never been properly inscribed.”

Could it be, then, Leader asks, that bipolarity is more common today, not simply because of good marketing by big pharma, but because we live in a culture that “pays lip service to history, yet which continually undermines the ties we have to the past”? Perhaps this is also why, Leader adds, bipolar today persists over the course of a lifetime whereas, historically, it was one of the forms of psychosis most likely to resolve over time. What we need is not so much increasingly fine-tuned meds for our various symptoms as the time required to explore our past in relation to our present difficulties.

6. Solms, Mark. The Hidden Spring: A Journey to the Source of Consciousness (2021).

Solms is a neuroscientist who also trained in psychoanalysis (one of the key founders of the journal of neuropsyhoanalysis) and this book summarizes his lifelong journey to understand how consciousness (specifically, self-consciousness) arises in humans and some other animals over the course of evolution. It is one of the most enduring questions of modern science. Why do you have a self that you experience as your self? Earlier theologians posited the existence of a soul to explain the presence of the self, and then neuroscience created the distinction between the (material) brain and the (existential) mind, but what exactly gives rise to this sense of self?

Solms, working within the same trajectory of Jaak Panskepp (who I have not read) and Antonio Damasio (who I have read), argues that self-consciousness is not rooted in the parts of the brain responsible for our most complex thinking (the neocortex). Rather, self-consciousness–and he goes through the science that demonstrates this–arises in the brainstem. Self-consciousness comes from the part of the brain responsible for emotions and affect. It is not thinking but feeling that gives rise to our sense of self (I feel therefore I am, would be Solms’s rebuttal to Descartes).

If this is where consciousness is situated, why did we evolve to have it? Well, Solms argues, feelings and affect allow us to respond quickly to complex situations in order to try and balance our various needs, including our need to survive. Were we to try and consciously and cognitively compute all the various ever-changing dynamics and risk-factors that we encounter moment-to-moment our brains would be overwhelmed and would require far more energy than we can provide to them. Thus, affect arises and uses prior experiences to help us feel our way through these situations (“This feels like [this other experience] which was [good/bad] and so I should respond [in this way]”). Feelings thus give rise to our bounded sense of self and become critical to survival, giving rise to beings who are self-conscious.

This, at least, is the core of Solms’s argument. It is fascinating and compelling and occassionally dense. Recommended reading.

7. Stuart, Douglas. Shuggie Bain (2020).

Shuggie Bain is a work of fiction that won the Booker Prize in 2020. It is roughly based on the author’s experiences of growing up gay in the 1980s in Glasgow, in poverty with an alcoholic, self-and-other-destructive mother.

It reminded me of Hana Yanagihara’s A Little Life (shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2015) and so I wasn’t altogether unsurprised to learn that Stuart published with the same literary agent at Yanagihara. It made me wonder if there is a genre of literature we should refer to as “trauma porn.” Just as splatter horror films have been referred to as “torture porn” because of the ways in which the directors and viewers get off on watching grotesque (and often sexualized) violence purely for the sake of reveling in that violence, it seems that some authors love wallowing in the miseries produced by horrible (and often sexualized) traumas. This certainly was the case with A Little Life (imo) and it’s why I did not enjoy it. It felt like Yanagihara was reliving her trauma fantasy over and over and over again for 800 pages. Almost like a “Fifty Shades of Grey” but for the literary cutters. Ugh.

I have been debating with myself about how much Shuggie Bain might also fall into this category. As a creative work, I definitely enjoyed it a lot more than I enjoyed A Little Life, although “enjoyed” may not quite be the right word. It is an unrelenting tragedy. A very real look at what happens when enforced poverty (Thatcher’s destruction of the miner’s union is in the background) meets loneliness, self-soothing through alcohol, toxic masculinity, rape culture, heteronormativity, and childhood all overlap and interact. It also, I think, treads somewhat less sentimentally through its subject matter than A Little Life. Perhaps it helps that Stuart lived much of this instead of simply fantasizing about it. A Little Life felt masturbatory–like pornified trauma. Shuggie Bain felt different. It captured the complex network of emotions that children of abusive parents feel–love, rage, a desire to help, a desire to give up and walk away, attachment, anxiety, brief and intense moments of hope and joy, and long drawn-out periods of sorrow and despair.

The book is well-written and very sad. If you want to feel very sad, I suggest you read it.

8. Van Der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (2014).

I decided to finally read The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van Der Kolk. Widely considered one of the top three classics in trauma studies (I think “Trauma and Recovery” by Judith Hermann and “Waking the Tiger” by Peter Levine are likely the other two foundational texts).

As famous as the book is, it is also notorious for being difficult to finish if you are a person who has experienced trauma or C/PTSD. It’s hard to work through a subject that will, inevitably, bring your own traumas, grief, loss, and experiences of abandonment or violence, closer to the surface. I found myself experiencing some nightmares and trauma flashbacks as I worked through this book. Reading a book alone and on your own is, in many ways, not ideal for processing trauma. Trauma injures our ability to connect with others and the world outside of us and so healing from trauma often comes, not by doing private, internal work, but by finding safe ways to re-establish connectedness and to be seen, heard, and understood by and with others. But, hey, sometimes the safest place we find for that is sitting with a book feeling seen, heard, and understood by the author. That’s okay if that’s where you’re at.

Taking many breaks along the way, forcing myself to not dissociate at times and also allowing myself to dissociate at other times, I am glad that I made it all the way through the book. It’s interesting that so many of the therapies Van Der Kolk recommends to the reader–EMDR, Neuroimaging, Internal Family Systems Therapy, Somatic Experiencing and Yoga–have all become fairly common and mainstream at this point. It’s also interesting how many of Van Der Kolk’s core emphases and insights about the need for individuals to receive sustained, long-term care that focuses on getting to the heart of *why* people feel, think, or act a certain way, have been neglected as mainstream community mental health services and psychiatry remain laser-focused on medicating symptoms in order to improve an individual’s functionality within the status quo or working, renting, and credit-debting. Van Der Kolk demonstrates how this is a massive betrayal of children and youth who experience violence and “developmental trauma.” As a society we are massively failing our kids. And, as Indigenous Peoples have always known, if we get this part of society wrong, everything else falls apart.

All in all, an excellent book although if you are going to read it with unresolved traumas of your own, I strongly suggest working through it with a group or a reading buddy.

Movies

Bailey-Bond, Prano. Censor (2021).

Censor is a film about a film censor in Britain in the 1980s who spends her days watching rough cuts of horror movies during the craze for extreme splatter gore–so-called “video nasties”–that went around at that time (think of movies like Cannibal Holocaust [1980] or The Driller Killer [1979]). However, things begin to unravel for the censor as the content of what she is viewing brings up a fundamental trauma she experienced as a child and her experiences of reality, dream, fantasy, work, and psychosis all begin to blur together. Stylistically, it is all very well done. Bailey-Bond does an excellent job in her debut feature-length film and Naimh Algar does an equally good job as the protagonist.

Watching Censor made me think (once again) about why a film does or does not get classified as a “horror movie.” Critics have classified “Censor” as a “horror movie” but Bailey-Bond calls it “an unnerving film about horror” and I think this is an important distinction (and one that applies to a lot of the so-called horror films I enjoy versus the mainstream horror films that I don’t enjoy at all). What makes Bailey-Bond’s contribution exciting and fun-to-think-with is that the horror she explores arises from within ourselves. It is the protagonist and her inability to be honest with herself if not about what she is or has not done, then at the very least about what she has or has not seen, that is unnerving and that points us into the heart of darkness.

2. Wan, James. Malignant (2021).

Speaking of mainstream horror films I don’t enjoy at all… I visit some fellows who live in a rooming house of sorts on the regular and we have a ritual of watching mainstream horror films together. Having had a few duds, we thought we’d maybe try to scare ourselves by watching James Wan’s latest contribution to the world of cinema (Wan is famous for the Saw and Insidious franchises as well as other pop horror films like The Conjuring, oh, and also: Aquaman). Anyway, the movie was a total bust and I’m continually amazed at how crummy big budget blockbuster Hollywood movies are. The story was all over the place. The acting was awful. The lighting felt like a snapchat filter. And when the evil parasitic twin emerged from the back of the protagonist’s skull and began to go on a kill-fest in the cop-shop, well, honestly, it was one of the most absurdly funny things I’ve ever seen. Don’t watch this movie.

Documentaries

1. Chin, Jimmy and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi. The Rescue (2021).

Jess and I watched The Rescue (2021) directed by Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi (they are a husband and wife duo). Focusing on the perspective of the expert British cave divers brought in for support, it tells the story of how twelve Thai boys and their coach were rescued from a cave in Thailand after becoming trapped there when early monsoon raids created a flash flood. When it comes to real life adventure documentaries, I’ve really enjoyed Chin and Vasarhelyi’s recent climbing documentaries (Free Solo [2018] and Meru [2015]). This one felt a little different, though, because they did not record the footage of the events themselves. Thus, it lacks their usual artist’s eye (although some scenes are recreated). And, moving from mountains to flooded cave tunnels, I think they struggle a bit to capture the same awe and wonder and also nail-biting tension and horror, that they are able to capture on larger canvases. To me, it felt like they were experimenting with their craft, working on expanded their skill set, and, while the content is compelling enough, I found myself feeling like the documentary didn’t meet the bar they have set for themselves. Plus, as Jessica reminded me, this story has been told before (in the 2019 documentary, The Cave, which we also watched although I had entirely forgotten that we did).

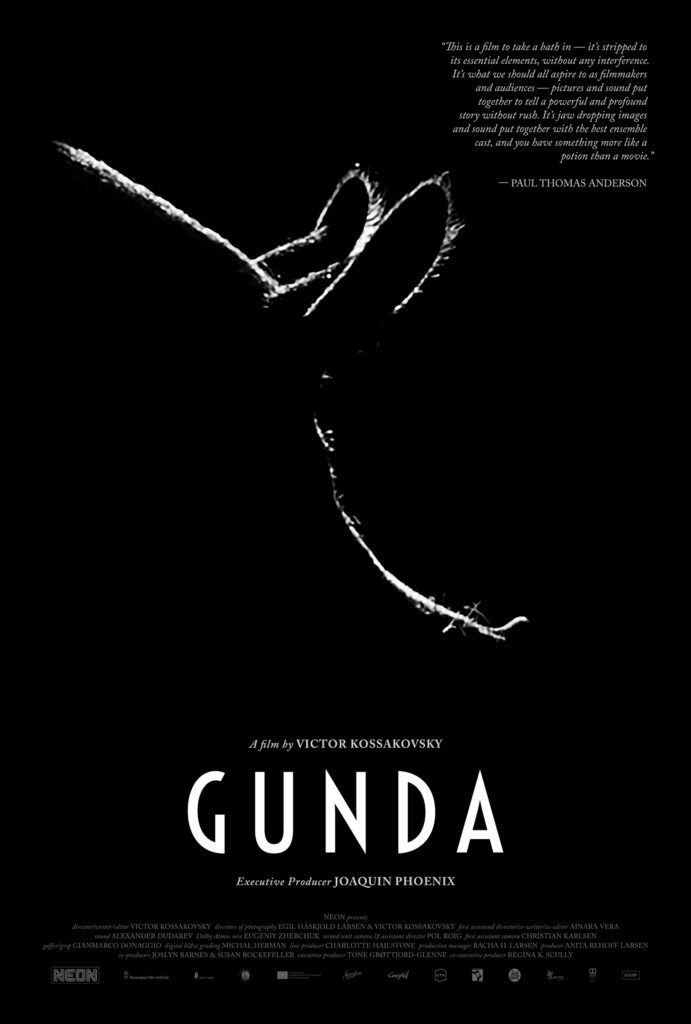

2. Kossakovsky, Viktor. Gunda (2020).

Over a period of several nights, I watched Gunda (2020) directed by Viktor Kossakovsky. Shot in black-and-white, with no dialogue or musical score, it’s a meandering and meditative piece about a mother pig and her litter of piglets (with a digression where we follow around a one-legged chicken and then some cows). In other words, not the fastest-moving film you will ever watch. In fact, it became a useful sleep aid. However, after watching Kossakovsky’s last documentary about water (Aquarela [2018]), I became convinced of two things: (1) few people have a better eye for film-making than he does; and (2) sometimes the slow meandering pace is misleading. Both of these lessons applied to Gunda. It is masterfully done and the meandering pace does lead to a conclusion that is truly devastating (and devastatingly true, I suppose—don’t by the lies you were told in Babe or Charlotte’s Web!). I’m not sure that many people will be able to get there but, if you do, it will leave you in tears–like Rachel weeping for her children and refusing to be comforted because they are no more.