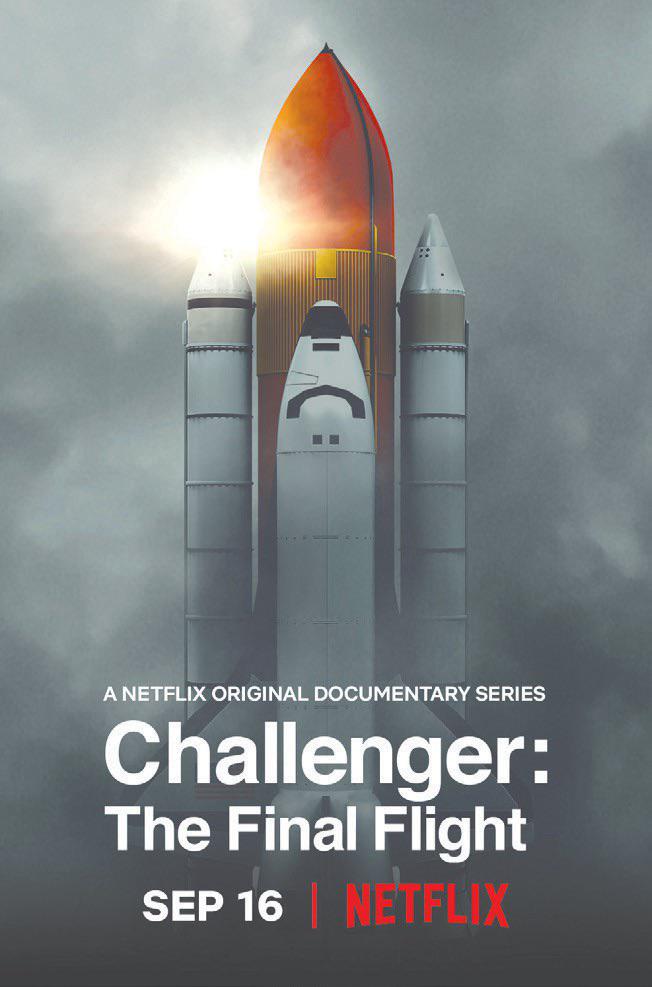

Discussed in this post: 17 books (Hermeneutics of the Subject; The Question of German Guilt; The Dark Side of Democracy; Border & Rule; The Vulnerable Observer; Entitled; Looking for Spinoza; Against the Loveless World; Girls Against God; Selected Poems; Patterson; An Africa Elegy; Ceremonies for the Dead; nedi nezu; No Heroics, Please; You Get So Alone at Times That It Just Makes Sense; and Scribbled in the Dark), 5 movies (The Sacrifice; Earth; The Wind that Shakes the Barley; The Turin Horse; and You Were Never Really Here), and 4 documentaries (The New Normal; Las Marthas; Roll Red Roll; and Challenger).

BOOKS

1. Hermeneutics of the Subject: Lectures at the Collège de France 1981-1982 by Michel Foucault.

The self-care industrial complex rarely if ever, to my knowledge, engages meaningfully with a Foucauldian analysis of society and yet, what do you know, the question of care of or for the self is the central topic of this lecture series offered towards the end of Foucault’s life. Rather than “knowing thyself,” Foucault argues that caring for the self is central to early Greek and then imperial Roman philosophical practices. However, this care of the self is a form of care that situates the self in a particular kind of relationship to the truth and so truth-telling is fundamental to this care. This, then, is not the self-care of the 21st century but is the kind of care for the self that one finds practiced especially by the Stoics, Cynics, and Epicureans. However, according to Foucault, Stoics like Seneca are developing an earlier model of self-care developed by Plato in the Alcibiades. For Plato, the sovereign is the one who must engage in self-care for when the sovereign cares for himself (yes, the sovereign is gendered as male), he is then able to also rule in a manner that is just. Later Roman thinkers then extent this model to suggest that self-care is something that all people, from all walks of life must practice in every stage of life through various (especially ascetic) practices. Self-care, then, has a lot to do with self-control rather than self-indulgence.

It’s interesting to read Foucault’s later writings, especially since I’ve been so grounded in much of his earlier work. It’s curious to see him take of the theme of how a subject might assay to situate itself in relation to the truth, given all the ways in which Foucault himself problematizes the question of the subject and the question of truth. I’m curious to see how he develops this theme in the few remaining lecture cycles that he completed before his death.

2. The Question of German Guilt by Karl Jaspers.

I am very interested in the question of what guilt Germans did or did not wrestle or reconcile themselves with after World War Two because, in my opinion, there are very strong parallels between the German experience and the Canadian experience. Both the Germans and Canadians built their nations in a way that ultimately required the deterritorialization, dispossession, and ultimately genocide of other peoples in their own homelands. Both the Germans and the Canadians then claimed stolen land as their own Heimat/homeland. Both the Germans and Canadians slaughtered millions—the Germans in a much shorter period of time but more explicit means; the Canadians over a much longer timespan using more subtle means. But the Germans were defeated. The Canadian occupation of Turtle Island, and the genocide against hundreds of sovereign Indigenous nations that accompany that occupations, both continue to the present moment.

After the war, the German people were confronted with the extent of what they did. And the Canadian people, too, have been increasingly confronted with the truth of what it means to be Canadian. Karl Jaspers’ examination of the question of German guilty post-WWII (who is guilty, in what way, for what?) is, thus, a question that can help Canadians understand their own guilty (if I am guilty, how am I guilty, how does my guilt differ than that of, say, an RCMP Officer, or the Prime Minster, or an Executive of Goldcorp?). Indeed, Jaspers’ argument is useful because it does not operate from a single monolithic sense of guilt but provides various nuances that, I believe, should help people both acknowledge their own guilt and then also have a better sense of how to move forward, NOT in order to be guilt-free (such a state is impossible and striving for such a goal can only ever throw our movements in bad directions) but in order to take responsibility for working towards creating a better future for everyone.

Sometimes, I play with the idea of writing a response to Jasper called “The Question of Canadian Guilt” but, um, time is rather limited for such endeavors these days.

3. The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing by Michael Mann.

The Dark Side of Democracy is Michael Mann’s companion volume to his earlier and very thorough overview of fascism. In this volume, he examines not just the genocidal elements of fascist regimes and their allies, but also other modern States—particularly democratic States—that engaged in acts of ethnic cleansing. Thus, from the exemplary genocidal cleansings of settler colonialism States on Turtle Island or in the South Pacific, to more recent genocides in the Balkans and Rwanda, Mann argues that “ethnic cleansing” is something that arises alongside of democracy, as it’s “dark side” (although the vast majority of genocidal actors are light-skinned…), and that States are most at risk of moving in this direction when two different conceptions of “the people” (the people as a nationality and the people as an ethnicity) are fused into one and then encounter other factors (threats from border regions, a search for a scapegoat for the failings of a nation, and so on). It’s a thorough study that, I think, contributes well to its field although, just as with Mann’s earlier work on fascism, is not without its problems. For example, while Mann examines the acts of German allies and occupied Nations in “the East” he entirely neglects the enthusiastic genocidal cleansing practiced by allies in Western Europe—most notably, the Vichy regime in France which, on several occasions, was far more enthusiastic about slaughtering Jewish women and children than even the occupying Nazis were. Why this gap? It appears to be inexcusable unless, that is, inclusion of those like the French upsets Mann’s model. Furthermore, I found Mann’s refusal to engage thoughtfully with the definition of genocide offered by the United Nations (or even with how discourses and definitions related to”genocide” and/or “ethnic cleansing” arose to be problematical. He assumes that genocide proper only means mass killing of a certain kind of people with the intent of exterminating them but there are many paths to extermination that, as the UN definition demonstrates, still count as genocide and Mann’s scaling back of referring to things in this way risks make extermination by, say, starvation, look kinder or less violent or whatever than extermination by machete. Also, given that this book was published in 2005, some of the failures of Mann’s model to predict where or how ethnic cleansing will appear have become apparent (just as Mann’s work on fascism can do a very good job of explaining the resurgence of neo-fascism in America today, leading Mann to view it has self-identified fascism that isn’t really technically fascism or whatever, which isn’t entirely helpful for forming political strategies and whatnot). The example of Modi’s rise to power in India is exemplary in this regard as Mann fails to see that India in 2005 was potentially well on its way to ethnic cleansing instead of seeing it as an example of a modern State where ethnic cleansing would not be able to fully occur (according, again, to his rather limited and limiting definitions). That said, I still enjoyed this book a great deal and learned a lot from him.

4. Border & Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism by Harsha Walia.

I am not given to the discourse of heroism and yet, despite myself, there are still a few people I have encountered in my life whom I cannot help but view with the kind of awe that borders on the heroic. Harsha Walia is one of those people and I have been beyond impressed by her dedication, thoughtfulness, valour, and ability to support communities of people who are oppressed to organize themselves to proleptically embody their own liberation. I had the opportunity to see her at work in the downtown eastside of Vancouver (illegally-occupied Coast Salish territory) and also participated in some of the events she helped to organize. I have always paid close attention to her words—whether those are coming from a bullhorn during a march, or are appearing in a newspaper created by people who have been colonized and impoverished, or in print in a book. Her first book, Undoing Border Imperialism was excellent and Border & Rule continues to apply her thought and the wisdom she has learned from others as the context in which we all struggle is continually shifting and, just as those who fight back get stronger and bolder so, too, do those who wish to push us all down and grind our bones into the earth. Walia’s particular strength is how her work with migrant groups (especially No One Is Illegal) meshes with her work with oppressed and impoverished female-identified folx (as in the Downtown Eastside Power of Women group) and her meaningful movement into solidarity with colonized Indigenous peoples. Add to that her super sharp mind and legal training, and you can understand why the cops and other agents of the Canadian State have been so explicit about the hate they feel towards her. She is a real threat. This book, which draws together all of these areas of her life and thought, is an excellent contribution to our collective work and one whose relevance will, I fear, only increase over the next few years. Recommended reading.

5. The Vulnerable Observer: Anthropology That Will Break Your Heart by Ruth Behar.

A lot of postmodern theory brought the subjectivity of the scholar and the situatedness of the researcher to the fore. Often, this was done to highlight the power dynamics involved with knowledge-production (and what even counts as knowledge, let alone who counts as a source of knowledge, as mon beau Foucault taught me) but Ruth Behar’s work jumped out to me because she wanted to explore not the power or privilege of the observer per se (although that comes up) but the vulnerability of the observer and how, bearing witness to certain things, often can (always should?) break your heart. It’s a topic I am very interested in, having had my own heart broken again and again in my work and research, but I was disappointed by this collection of essays, which felt somewhat meandering and a bit lost to me. Which is fine. I’m all for getting lost and wandering in our observations and telling stories because we have started them and are not sure where they end or if they have a point or if they need one, it’s just I brought the wrong expectations to this book.

6. Entitled: How Male Privilege Hurts Women by Kate Manne.

Learning to do intersectionality well, and to move from the bougie (and mostly bullshit) Liberal politics of allyship to a more desirable and appropriate politics of accompliceship is hard work for the Whites. I know. It is and continues to be a lifelong journey for me. So, here’s the thing. Kate Manne wrote one of the best take-downs of how misogyny works within the overall context of patriarchy with her last book, Down Girl. Easily one of the most significant books I have read in the domain of critical theory. So, so damn good. But the book presented a fairly bleached-out politics valourized White feminism, especially with its praise of Hillary Clinton and no thought of how brutal Clinton’s approach has been to BIPOC women in American-occupied territories (both on Turtle Island and elsewhere). So, after following Manne and her work, I really wondered how she might engage with BIPOC criticisms of White feminism (Ruby Hamad’s White Tears/Brown Scars, for example) or with voices from the Queer and especially trans communities who object to much of the gender essentialism of White feminism. So when Manne explicitly states she intends to engage in form of feminist criticism that prioritizes intersectionality and centres voices from Queer, trans, and BIPOC folx, I was all for it. Great! Here’s one of the most brilliant feminist thinkers now engaging a topic I have wondered a lot about in relation to her work. This should be excellent, right?

Well, no, not exactly. Because Down Girl really went boom. It became a best seller. And best-selling authors face a lot of pressures to produce another work while their brand is hot and when people are thirsty to read more of them. And Entitled went on to sell very well (and garnered praise mostly, I think, by people who really wanted to just praise her first book). But it reads like Manne went back and revisited her research notes for Down Girl, added claims to intersectionality (which mostly amounted to saying things like, “and what I’ve described is even harder for Black or Brown women or trans-identified people”—i.e., nothing substantial and nothing that really meaningfully engages BIPOC criticisms of White feminism, and then quoting more BIPOC women as sources [while still reinforcing gender essentialism in some passages], while switching from Hillary Clinton to Elizabeth Warren whom Manne quickly forgives for the indiscretion of falsely claiming Indigenous status). It’s disappointing and, in fact, risks falling to the criticisms raised about how White feminists who claim to want to centre BiPOC women actually end up just continuing to centre themselves.

My hope, then, now that Manne is well-established and has two successful books under her belt, is that she will now go and revisit some of these themes with the same thought and care and brilliance that she put into Down Girl. I still have high hopes for book number three.

7. Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling Brain by Antonio Damasio.

Antonio Damasio is a neuroscientist who likes talking his feelings. And all of our feelings. And why in the world do we have feelings anyway? From an evolutionary perspective, where do feelings, specifically feelings that relate to emotions, come from and what purpose do they serve? Well, Damasio suggests, feelings and emotions can be useful things to help complex organisms respond to large amounts of data and stimuli, while factoring in past experiences, in order to help an organism quickly move towards thriving and away from threats of harm. One of the particularly interesting conclusions of Damasio’s research is that the conscious thought that “I feel happy right now; that is because…” or “I feel sad right now; that is because…” actually comes at then end of a process of feeling that feeling for reasons that may or may not be related to what we identify as the source of our happiness or sadness. That is to say, all of our senses are constantly absorbing all kinds of information from the world around that and is responding to that information based upon our past experiences (hence, of course, the whole thing in trauma studies about how “the body keeps the score”). The body, then produces certain feelings in response to this and, if these feelings build-up in self-reinforcing feedback loops (which can be produced very rapidly) we then become conscious of the feelings and our conscious mind produces an explanation. We then tend to think that we feel a certain way because of this explanation but this is precisely backwards—it is because we feel a certain way that the explanation is produced. Fascinating stuff.

8. Against the Loveless World by Susan Abulhawa.

In less recent years, I spent a lot of time learning about Palestinian history and politics as I was kicking it with some Palestinian friends and wanted to understand more about the theft of their land, the illegal occupation of Palestine, and the genocide the Israelis have directed against them (and which the Israelis continue to perform up to the present day). However, a few years ago, I found myself thinking, I don’t want to just read Palestinian history or politics—I also want to see Palestinian art, hear Palestinian poetry, read Palestinian literature. I want to know more about the heart of the people, and not just learn about the people as stats or facts or records. And so, this month, I picked up Susan Abulhawa’s book, Against the Loveless World. I very much enjoyed it. I think it helps to capture something of the complexity of the Palestinian experience and pushes back against and Occidental prejudices and stereotypes that flatten out the experience of “the Palestinian” or “the Arab” or “the Muslim women” or “the freedom fighter/terrorist” within the kind of orientalism that Edward Said so cogently criticized. I look forward to going back and reading her Mornings in Jenin.

9. Girls Against God: A Novel by Jenny Hval.

I had high hopes for this hot-take on Norwegian literary horror. But I think it was geared more towards hipsters. Who are more concerned about the pretension. Of avoiding pretentiousness. And care less about content. Than about what others say about the content. While acting like they don’t care. What others think. But me? If you ask my future wife—a women against god of the best kind—I am not a hipster. I’m just stuck in the ‘90s. And maybe that’s why this book didn’t stick with me.

10. Selected Poems by William Carlos Williams.

This is just to say

I have read

The poems

That are in

This book

And which

My friend Daniel

Suggested

I read

Thank you

They were delicious

So clever

And so not-as-boring-as-other-poems-can-be

11. Patterson by William Carlos Williams.

Although I am not inclined to read (or enjoy) epic poems, Jim Jarmusch’s film rendition of Patterson, combined with my enjoyment of some of WCW’s shorter poems, made me curious enough to read the poem itself. What can I say? Jarmusch did a good job.

12. An African Elegy by Ben Okri.

Okri is an author whose literature often sounds like poetry. The Famished Road is a beautiful work that, to me, melds poetry with prose in a way that is hard to do but when done well, as Okri does it, produces some of the most delightful books to read. So, given that, and given that I had previously come across references to Okri’s African Elegy as a politically-significant and poetically-beautiful cri de Coeur, I thought I would check it out. I enjoyed it, although I found that I have enjoyed Okri’s novels more.

13. Ceremonies for the Dead by Giles Benaway.

The dead are everywhere these days. My friends and companions who continue to suffer impoverishment, abandonment, housing deprivation, and the criminalization of their medication and healthcare, are dying at rates I have never seen. Just this week, six people died. Three in one day. Covid lockdowns, when mixed with neoliberal housing strategies, long and ongoing histories of colonization, and a war on drugs (which is really just a war on people who can’t clear the high barriers that exist in order to access healthcare and who then try to find their required medications by other avenues), are extremely lethal. I fear my dead now outnumber my living. And, Giles, Benaway, too, is aware of the great host of dead who abide with us. Who remain. Who are a part of this land. For Indigenous people on occupied Turtle Island, their dead have vastly outnumbered their living for many generations. What does it mean to abide in this kind of company? What kind of relationships should one have with the dead? Benaway asks these questions. I think all of us should.

14. nedi nezu (Good Medicine) by Tenille K. Campbell.

Tenille Campbell writes poems that, to me, strike a perfect balance between literary craft and eroticism. As In noted last month, what people look for in erotic art (versus, say, eroticism shaped by market forces) is notoriously difficult to standardize but, to me, Campbell really nails it. Sex and lust and fucking and love and desire are complicated things. Delightful and not always so. Mixed up with other things like race and class and patriarchal heteronormativity and settler colonialism they only become more complicated. And yet they persist. And the goodness that can be contained in them also persists. Even if it is not always where we hope to find it. Recommended reading.

15. No Heroics, Please: Uncollected Writings by Raymond Carver.

There are writers whom I encounter who make me want to read their everything. Raymond Carver is one of those writers. His short stories haunt me and his poems often fall to land with me but when they do, they are amongst the best of the best of the best. As a result, I have found myself obsessively reading through his work as I have done with others (W. G. Sebald, Cormac McCarthy, Margarita Karapanou…). However, as with others, publishers like to take advantage of this kind of obsessive literary fanbase and pump out volumes that don’t necessarily meet the same standards as other works because they know people like me will buy them. I would say No Heroics, Please is that kind of book.

16. You Get So Alone At Times That It Just Makes Sense by Charles Bukowski.

I like Bukowski’s poetry. I’m not sure if I like that part of me that likes Bukowski’s poetry. I go back and forth on how much I care about that. Shadow self and all that, ya know? Anyway, as I was reading this collection, I sat down and penned this poem:

All Is Not Yet Lost

On the balcony of my brother’s apartment

I forget if I was smoking

But I spent a lot of time then

Alone and quiet and thoughtful

Most especially late at night

And early in the morning

But leaning on the railing

Of the balcony of my brother’s apartment

I was wondering about the feeling

Of flying like a flightless bird

Towards the concrete flagstones

Three hundred feet below

The morning sun just cresting

Over the college across the road

When the curtains in a window

Of the building to my left

Opened

And a young topless woman

Looked out upon the day

All is not yet lost

I thought and held my breath

Until I nearly died

Happy

But didn’t

And maybe you will like that poem. And maybe you will hate it. I could go either way on it myself. But I wrote it nonetheless.

17. Scribbled in the Dark by Charles Simic.

As some of my readings reflect, since reading Rebecca West’s book about the Balkans (Black Lamb and Grey Falcon) as well as some of my previous WWI history readings (I realized a few years ago that I really knew nothing about that event which I found curious given its importance for the history of the 20th century), I have become increasingly interested in this part of Europe. So I picked up Simic’s poems because, to be honest, I had him confused with another poet who wrote about the genocidal war that occurred there in the ‘90s. Still, Simic’s poems were playful. I enjoyed them in the way one might enjoy a passing pleasure before moving on to something else.

MOVIES

1. The Sacrifice (1986) directed by Andrei Tarkovsky.

Tarkovsky is a serious fellow. People talk about serious things in his movies. A lot of the time they talk to themselves about those things. The music is also very serious. If you want to watch his movies, you will need to take them seriously. Seriously. And sincerely. Tarkovsky is nothing if not sincere. You should watch Tarkovsky a lot when you’re seventeen and want all your conversations to be about what really matters in life and you can’t stand all the rom-coms and sit-coms your friends watch. Maybe contemplate your own mortality and put on some black lipstick before you put the movie on. I regret not doing that before watching this film. Like I said, this is serious.

2. Earth (1930) directed by Alexander Dovzhenko.

I mostly watched this movie to admire the homemade blouses worn by the male peasants and the beautiful needlework that was on them. I really wish I just wore blouses like that with vests. But, yeah, Dovzhenko’s film is one that his highly praised by the critics in relation to the history of film. To me, it was a brief glimpse into a world that no longer exists. The scene that stands out the most to me was the one of the peasant dancing a traditional Ukrainian peasant dance. It made me wonder about similarities and differences between traditional dances across cultures and large spans of geography. In part, because it reminded me of traditional Roma dancing I have witnessed as well as jingle dress dancing I have observed at Powwows. Anyway, I wouldn’t recommend this film if you are looking for a movie to watch but, as a glimpse into a history that is gone, it’s enjoyable.

3. The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006) directed by Ken Loach.

Ken Loach is a director I decided to follow after I watched the truly remarkable I, Daniel Blake. I’m late to the game with him and his work but I want to catch up! So, given that some folx were celebrating St. Patrick’s Day this month, I decided to watch this movie about Ireland in 1920, during the War of Independence, when the Government of Ireland Act was created. This Act that helped divide the Irish so that the Irish went from fighting as united front against England to fighting each other about how to best be free from England. Loach shows the depth and pain and of this struggle and also the ensuing division by focusing the film upon two brothers and the small group of co-conspirators who met with them. It is a deeply moving film. It had me reflecting on my own life and how involvement in life-or-death struggles, wherein those struggling are motivated by closely held and intimately personal values, can lead people who love one another dearly to end up hurting each other and even, at times, fighting against one another. War is hell and it splits loved ones apart despite their desire to be close together and the sacrifices it forces from you are not the ones who expected or desired to make but the ones that you did not want, would not choose, and regret with all your heart. War is hell and that’s just as true of the wars of colonization as it is of the wars that neoliberalism wages against those whom it dispossesses.

4. The Turin Horse (2011) directed by Béla Tarr.

The adult daughter of an older man helps him change his clothes. They then eat potatoes together. The wind blows. The soundtrack loops. This happens very slowly, nine or ten times over the span of two and a half hours. We watch it in beautiful black and white. Nobody says much of anything. There is a horse. The movie ends. It is Béla Tarr’s last movie. Think what you want about that.

5. You Were Never Really Here (2018) directed by Lynne Ramsay.

I’m still figuring out what I think about Lynne Ramsay’s work. I enjoyed Morvern Callar (Harmony Korine totally ripped this off for Spring Breakers), still need to watch Ratcatcher, and very strongly disliked We Need to Talk About Kevin (which was highly praised by the critics but which I hated for reasons I’ve already described so won’t get that again). Given that the last film was her more recent one, and given that, You Were Never Really Here ticks a lot of boxes about movie themes I distrust (tortured White man saves pretty White girls from evil sex traffickers… ugh), I didn’t rush to watch it despite all the praise it received (I suspected Ramsay of simply continuing to exploit whatever cultural trauma or fear is trending—from high school shooters to the sexual trafficking of little White girls [even though, of course, Indigenous women and girls, as well as women and girls from other racialized groups are far more likely to be victims of this kind of trafficking and, of course, most victims of human trafficking are trafficked for nonsexual, labour-related purposes and, of course, the whole discourse of trafficking is entirely whorephobic and abusive and used to increase the surveillance and power of the police and carceral states]). But, okay, I have been increasingly impressed by Joaquin Phoenix’s acting and my curiosity about what to think of Ramsay got the better of me the other night (I mean, Morvern Callar was really good). Both do very good work with this film, despite the limitations and problems imposed by its overall theme. I was very worried about the potential sensationalization of the (sexual or not sexual) violence, but I liked that Ramsay left most of that off screen or just out of site. In mean ways, in my opinion, that better captures the incommunicable immensity of some acts of violence. Some kinds of a violence cannot be communicated on a television screen. They are more like an immense mountain that you can circle around (over a series of days), the peak sometimes visible, sometimes shrouded in cloud, the whole thing just too big for you to take in all at once.

DOCUMENTARIES

1. The New Normal (2020) directed by Codi Barbini.

Previous school shooter documentaries have tended to focus upon the factors that produce school shooters (Bowling for Columbine being a prime example) or that focus upon family members who lost their children and how their lives were changed even though society was not (Newtown being the obvious one here). Codi Barbini takes a different tack and focuses on other students who were present at the high school in Parkland, Florida, on February 14, 2018, when fourteen students and three staff members were shot and killed.

2. Las Marthas (2014) directed by Cristina Ibarra.

Las Marthas, a documentary film about a border town predominantly populated by Mexicans and Mexican-Americans which engages in an extravagant series of events to celebrate George Washington’s birthday every years, has found a rich terrain that could be explored in all kinds of directions at once. In many ways, it offers an excellent companion piece to Harsha Walia’s book (mentioned above) and demonstrates the complexities related to the ways in which border imperialism interacts with class, capitalism, cultural conceptions of beauty, and heteropatriachy, to produce some (at first glance) seemingly contradictory subjectivities–like wealthy Mexican families living in Texas, living off of oil profits, and celebrating American nationalism with far more extravagance than most others. However, I feel like Ibarra gets a bit distracted by the spectacle (and it’s so easy to be distracted by the spectacle) which, of course, is massively entertaining. It’s also deeply troubling and Ibarra flags that, shows that in some ways, but doesn’t dwell there because, holy crap, that’s a $50,000 dress and it weights 150 pounds! One day, I think somene really smart will watch this and say really smart things with and about it. That day is not today though.

3. Roll Red Roll (2018) directed by Nancy Schwartzman.

Rape appears to be the ubiquitous theme in Netflix documentaries this year and last. In part, I think this has something to do with the success of the #metoo movement and how this has shifted areas of public focus. In part, I think, because people in general have always had a strange fascination with sexual violence (sex sells, violence sells, sexual violence sells times two). And, in part, in my opinion, because rape is ubiquitous and real life and, since almost nobody is talking about it in real life, we are left processing it through various other media.

Roll Red Roll is an extremely difficult documentary to watch. It recounts how a group of cis-gendered teenage boys gang-raped a teenage girl while she was unconscious and then, for the most part, joked and laughed about it, distributed pictures of it, and basically thought it was the funniest thing ever, and were then supported and protected by the adults in their lives who became aware of it. It demonstrates how rape culture is American culture is sports culture is cishet culture, is small town White culture.

Also, the ability of these cis-gendered teenage boys to “code switch”–to laugh uproariously at the most shocking and offensive rape jokes they can concoct in one moment and then to be polite, upstanding citizens, with a firm sense of right and wrong and a profound respect for women when they are filmed being interviewed by the detectives–demonstrates that, although young cis-gendered men or boys rape, they do so, in almost every case, knowing that they are doing something they should not be doing, something for which there are, at least, consequences they will not enjoy experiencing if they are caught. Maleness and masculinity is so adrift and death-dealing in our culture. It causes me considerable despair.

4. Challenger: The Final Flight (2020) directed by Daniel Junge and Steven Leckart.

Highly praised as one of the top docuseries of 2020, Challenger tells the story of all the reasons why NASA knew it should not launch Space Shuttle Challenger on January 28, 1986, why it did so anyway, and who did and did not pay the price for that. As with most disasters related to government projects, the little people saw the disaster coming, were ignored or co-opted just enough to make them accomplices in the disaster, and then paid the price, either with their lives or with a lifetime of guilt, loss, and trauma, while the big people prioritized profits, pride, and position over the lives of others and pretty much all got away with it while still feeling great about themselves.