Discussed in this post: 14 Books (Phenomenology of Perception; Ethical Loneliness; How Europe Underdeveloped Africa; Canada in Africa; Tomorrow’s Battlefield; Lamarck’s Revenge; The Wild Places; Noopiming; Laurus; EEG; Fatelessness; Wicked Enchantment; Postcolonial Love Poems; and Ban En Banlieu); 4 Movies (The Wolf House; Hagasuzza; The Handmaiden; and Cargo 200); and 3 Documentaries (Welcome to Chechnya; Cheer; and The Painter and the Thief).

Books

1. Phenomenology of Perception by Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

The good thing about this review of Phenomenology of Perception is that is will be significantly shorter and significantly less boring than the book itself. What can I say? Well, there are some classic theory books that will test you and challenge you long after they were written (say Being and Time if we want to stay in the domain of phenomenology), but there are other classic theory books that were innovative and ground-breaking at the time they were written, but now their central innovative conclusions have become taken-for-granted starting points for subsequent theory. I feel like some of the latter is going on with this work by Merleau-Ponty. Breaking down the previously taken-for-granted by wall between “the self” and “the world” (or “the organism” and “the environment” if you want to use eco-evo-devo language) or “the mind” and “the body” or “thought” and “sensation” is great for busting through some of the stupider presuppositions of modern European philosophy (as was the trend in the ‘60s) but I’m not sure if one needs to spend 500 pages working through all of this at this point. Probably a 5-10 page summary would be adequate.

2. Ethical Loneliness: the injustice of not being heard by Jill Stauffer.

Sometimes I accidentally fall back into readings that relate to the Holocaust. There was a time when I deliberately sought out content about that event and there was a time when I deliberately stopped seeking it out, but I find I keep coming back to it. Which is interesting and makes me feel a bit like a person-out-of-time or, at least, out-of-my-time, since the Holocaust was one of the definitive (if not the definitive) event of the time before mine and became less so in the time that was mine, and (it seems to me) much, much less so in the time after mind (which, I think, is the time we are in now). Nonetheless, Stauffer’s book on ethical loneliness and the injustice of being heard, brought me back to the Holocaust via Jean Améry and Emmanuel Levinas. Here, she examines what happens to people who both experience a devastating trauma, loss, or experience of utterly dehumanizing violence, and, after the fact, experience what it is like to not have their voices heard about what they experienced. This produces what Stauffer refers to as ethical loneliness. To overcome such loneliness, Stauffer highlights the importance of resentment, the refusal to forgive, and the failures and shortcomings of state-sanctioned truth and reconciliation commissions (here, Stauffer looks at South Africa, the Balkans, and Argentina, but Canadians would do well to attend to her words here—hell, I would argue that Canadians have a moral obligation to attend to her words her). I think this is a very important work and one that is both a much-needed alternative and potential cure for the sickening calls for forgiveness and reconciliation that are ubiquitous in the ongoing colonization of Turtle Island.

3. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa by Walter Rodney.

A classic work of decolonizing (Marxist) theory, Walter Rodney’s book on how Europe underdeveloped Africa was the first book I turned to this month with the intention of broadening and deepening my understanding about the political and economic history of that continent. It’s an excellent overview and general history, even if it is a bit too committed to hard-and-fast Marxist categories and historical determinism. Rodney, in other words, fails in his predictions about the future of many African States, but he does a very good job of explaining the history to preceded those States and why they are the way that they are—and why European States built their so-called greatness on the dispossession, impoverishment, exploitation of Africa, establishing systems and structures that ensure that the gap between Europe and Africa will continue to expand even if African States follow a neoliberal model of “development.”

4. Canada in Africa: 300 Years of Aid and Exploitation by Yves Engler.

Some people writing about politics, history, and economics, are able to write real page-turners that are brilliant, informative, and keep you coming back on the regular (Walter Johnson’s The Broken Heart of America jumps to mind as a recent example of this). Others who write in these fields can be super dry and sound like they are just reading you lists of stats, dates, numbers of people affected, location where they were affected, and, yeah, important information, good to know and all that, but dang a bit dry. Having read a few things by Engler now, I feel like he falls into the “dang a bit dry” category. Which is too bad because tracing the history of Canadian imperialism, especially through its so-called “peacekeeping” missions and the actions taken by it’s massive mining corporations along with so-called “aid” dollars (that mostly just go to being weapons and training police and soldiers who are hired by governments who support Canadian corporate interests), is actually an important thing to do. Although, even here, I feel like Engler could have done a bit of a better job (for example, earlier on in the book, when Engler talked about the actions of this-or-that individual Canadian, who could have done a better job of linking that back to Canadian-ness or the project of Canadian imperialism more broadly). However, given how little Canadians tend to know about this fundamental component of what it means to be Canadian, this text still remains strongly recommended reading for my fellow colonizers and imperialists.

5. Tomorrow’s Battlefield: US Proxy Wars and Secret Ops in Africa by Nick Turse.

I’ve followed the TomDispatch news site on and off for years and I have often appreciated their reporting. Given that one of my reading goals for this month was to learn more about African history and politics, I thought I would pick up this book by Nick Turse (of is a regular contributor to TomDispatch) because I remember reading some very informative articles he wrote about the African continent and American involvement there. I also felt like this would help me to understand more about how contemporary warfare has increasingly shifted from mass military mobilization to smaller scale, “low intensity” conflicts and special operations. And, yeah, this book does provide some useful information in that regard. But that’s because it’s actually just a collection of the articles Turse wrote on TomDispatch (and that I think I read when they went online). As such, it’s fairly journalistic and highly repetitive. I should have checked the table of contents more thoroughly before purchasing this one. I was hoping he was drawing together the work he had put into those articles to build a more sustained case or more thorough argument, but I was wrong about that. Oops.

6. Lamarck’s Revenge: How Epigenetics Is Revolutionizing Our Understanding of Evolution’s Past and Present by Peter Ward.

Epigenetics or heritable genetic variation—wherein the experiences and even state of mind of a parent organism can cause heritable changes to both the genotype and phenotype of offspring organisms—was an idea proposed many years ago by Jean-Francois Lamarck but mostly entirely rejected by classical Darwinian evolutionary theorists (and by many contemporary neo-Darwinians). However, it turns out that Lamarck was actually onto something (even if he was totally out to lunch with his idea that extinction wasn’t a thing… admittedly, a pretty whacky idea to us now although, hey, people were still figuring out what the fuck was going on with the earth and the fossil record up until not that long ago—and it’s not like we have it all figured out now, but that’s a tangent). What we know now about DNA-methylation and the ability for rapidly-changing mutations (sometimes positive, sometimes neutral, frequently negative) to occur within the genotype and phenotype of organisms actually confirms much of what Lamarck had to say about heritable genetic variation (something agriculturalists and breeders have long recognized with crops and certain breeds of animals of course). This also goes a long way to explaining sudden explosions of life (say the Cambrian explosion) or the remarkable emergence of incredibly diverse lifeforms that do not show up in the fossil record but which appear almost immediately after mass extinction events. What Ward suggests (rather convincingly) is that, when things are going along relatively smoothly the Darwinian model of evolution dominates but when everything goes fucking bananas, environmental and stress-induced changes to organisms cause far more genetic variation to be produced which, while often leading to large die-offs (because we’ve evolved as very complex networks of organisms and so a shift in an organism or in that network can seriously compromise survivability), can also lead to various different forms of organisms that are able to survive in environments that were largely not survivable to the organisms that existed previously. It’s a fascinating thesis and a great read, if even it felt like Ward added a few of the later chapters just to fill the whole thing out a bit and a make proper book out of the content he had. This is most definitely a subject that fascinates me—both because it inspires awe in me and, no doubt, because it offers us hope in the seemingly hopeless context of living and dying within the Sixth Mass Extinction of life on earth.

7. The Wild Places by Robert MacFarlane.

In the midst of many sorrowful circumstances and the busy-ness of life, the writings of Robert MacFarlane continue to be something that feeds the gratitude, wonder, and desire for peace and beauty within me. I don’t have much else to say about him that I haven’t already said about his other books (or when I picked him as my “best of the year” for my 2020 readings). As the Scottish mountaineer, and concentration camp survivor W. H. Murray, whom MacFarlane is fond of quoting once said, “Find beauty. Be still.” Reading MacFarlane helps me do that. That makes this kind of reading not just recommended but, for me, essential.

8. Noopiming: The Cure for White Ladies by Leanne Betasamosake Simpson.

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg) remains one of my favourite contemporary authors working in the borderland between fiction and non-fiction, traditional knowledge and contemporary theory. Noopiming is an Anishinaabemowin word meaning “in the bush” and the book is an explicit shot at Susanna Moodie’s, White, colonial memoir, Roughing It In The Bush that mixes humour, brilliance, sorrow, joy, and rage in a wonderful blend that doesn’t simply strive for decolonized ways of speaking but which demonstrates what it means to tell decolonized stories in a colonized land. A most excellent book.

9. Laurus by Eugene Vodlazkin.

All though a lot of my interest in Eastern European literature has shifted from Russia to other smaller states, I sometimes try to check out what is going on in Russian lit. My last foray into that realm was an unmitigated disaster (I got two thirds of the way through Sorokin’s Ice Trilogy and then, in a rare move for me since I’m pretty obsessive about finishing stories I start reading, I abandoned it because it just felt like uber-repetitive pulp fiction wherein the author simply relived the same fantasy over and over and over and over again). However, I liked the reviews I read about Laurus and the ways in linked to some of the more philosophical or spiritual aspirations of Russian authors and mystics and so I picked it up. It was an entertaining read, straddling the line between magical realism and postmodern literary criticism with a distinctly Russian twist. I know Vodlazkin has been compared to Umberto Eco, but I think perhaps he is closer to a blend of Marquez and Calvino although I feel like that might slightly over-estimate his abilities. A good read nonetheless.

10. EEG by Daša Drndić.

Daša Drndić has been described as a “neo-Borgesian” but I think it is more fruitful to see her as a Croatian compliment to the work of W. G. Sebald. Both circle around the monumental but also capillary and interstitial violence of 1939-1945 and do so in a way that is difficult to classify in terms of an overly simplistic fact or fiction binary. But while Sebald is interested in German and Western Europe, Drndić is focused on her homeland—the Balkans. Futhermore, while Sebald goes to the country o find the traces and enduring legacy of great violence in the landscape, Drndić goes to the towns and cities and and the family histories of herself, her friends, her neighbours, the grocer, the person who lives up on the hill. Perhaps it is this geographical shift, and what comes with it, that is both born from and leads to Sebald’s melancholy and Drndić’s outrage. Drndić, in other words, has moved into the category of author’s whom I want to read voraciously. EEG is a difficult work to classify or describe (I can’t imagine how one might try and pitch it to a publisher if one was not already an established author) but it is remarkably good. I am excited to go back to her earlier works, Belladonna and Trieste, and see where they take me. High recommended.

11. Fatelessness by Imre Kertész.

Continuing my tour through Eastern European lit, as well as finding myself inadvertently falling deeper into reading about the Holocaust, I read Kertész’s Hungarian memoir about his time as a teenager in Auschwitz and Buchenwald. Comparisons to Primo Levi are apt. Simple prose, difficult reading. Bearing witness is hard. Both for those who testify as to what they have seen and for those who bear witness to that testimony. And yet I think often about these things, especially in relation to my own work in institutions that surveil, enclose, and shelter people today who are abandoned and left for dead. Beware the trajectory of the camps. Remember, remember how often social workers and healthcare professionals have made great violence possible, reasonable, and morally plausible.

12. Wicked Enchantment: selected poems by Wanda Coleman.

A lot of people like Wanda Coleman’s poetry. It’s gritty and literary (gritterary??) all at the same time and speaks from the margins in a way that triumphs over the centre on the centre’s own terms without, somehow, capitulating to the centre. So that’s pretty great but, ya know, I tend to read poetry less as a critic and more as a person seeking a certain kind of affect (I am, for the most part, an entirely selfish consumer of poetry) and I struggled with this collection in this regard. Great poetry—don’t let me lack of taste put you off—it just didn’t ring my bells.

13. Postcolonial Love Poems by Natalie Diaz.

However, Natalie Diaz’s poetry really did ring my bells. She touches upon a lot of the same themes as Coleman—but while Coleman writes from an impoverished portion of Black LA, Diaz writes from the rez—but I resonated so much more with her voice. In comparison to Coleman, it felt less Diaz wasn’t nodding to the conventions of “literary poetry” (which is not to say that she actually wasn’t nodding to those conventions in smart and subtle ways—it just felt less like she wasn’t) and maybe I’m a sucker who feels like that somehow makes a poem feel more “genuine” or “raw” but I think there is more to Diaz’s craft than that. I’m still trying to understand what or why that is.

14. Ban En Banlieue by Bhanu Kapil.

I returned to Bhanu Kapil after reading humanimal because I felt like she was on the verge of something inexpressible there and yet, somehow, I felt like she didn’t quite accomplish what it felt like (to me—obviously a highly problematical statement given where her and I are situated) she wanted to achieve. Kapil’s writing reminded me a bit of projects produced by incarcerated victims and survivors contributing art to the anti-psychiatry and Mad Pride movement(s). Clearly something brilliant is being worked out in this person’s mind—but my psychosis (or sanity or whatever) is slightly too different than theirs for me to be able to fully work out what they are getting out. So, learning that Ban En Banlieu was somewhat more autobiographical, I thought that perhaps I might be able to make better sense of what Kapil is doing. But I was wrong. For me, she remains a near miss. Which, no doubt, is completely fine with her.

Movies

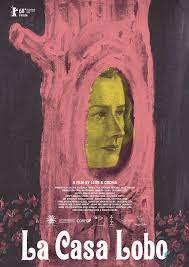

1. The Wolf House (2018) directed by Joaquin Cociña and Cristóbal León.

After WWII, the Nazi medic and unrepentant pedophile Paul Schäfer become a devout Baptist and fled to Chile where he founded Colonia Dignidad, an extreme Christian cult, that sheltered many other fleeing Nazis, including (briefly?) Dr. Josef Mengele, “The Angel of Death,” who was notorious for doing medical experiments on prisoners at Auschwitz. Then, when Pinochet came to power, Schäfer and his community participated in disappearing, locking-up, torturing, and murdering Chileans targeted by the regime. Schäfer also went on to connect Pinochet with German black market arms dealers. Schäfer was able to hold-on to charitable status for his Colonia up until 1990 although, again, pedophilia was rampant in the community and local Chilean children who were sent to the hospital there were raped by Schäfer. He was forced to go into hiding in 1997 (he hid in a wealthy, gated community in Argentina—another Nazi hotspot with connections to Mengele and Eichmann) and was finally jailed in 2005. He died in jail, at the age of 88, in 2010.

The Wolf House, created over several years by the Chilean directors Cociña and León, is a staggeringly brilliant and dread-full stop-motion animation fairy tale about this. It is a visceral presentation of how those who are traumatized encode, retell, and reckon with trauma. It belongs in equal parts in political studies, in trauma theory, in art, and in horror. This is like Jan Švankmajer’s version of Alice in Wonderland (called Alice), only all that is surreal and unreal is actually a more honest way of representing the unspeakable and incommunicable than we we find in photographs or treatises. I could not look away. Even if I sometimes wanted to.

2. Hagazussa (2017) directed by Lukas Feigelfeld.

Folk horror, when done well, is one of my favourite genres of film. Hagazussa, with its beautiful haunts, well-crafted costumes, and top-notch cinematography was high on my list of hopefuls. Sadly, I found it fell short in terms of (what I like to see in) plot and character, and while it aimed to provide the viewer with a story that invited multiple, inconclusive interpretations, it actually felt like a somewhat sporadic collage of dead-ends and thoughts that the director didn’t quite know of to combine or complete. That said, I ate a roast chicken the day after I watched this movie and I wasn’t able to finish it because, well, if you’ve seen Hagazussa you know why.

3. The Handmaiden (2016) directed by Park Chan-wook.

Eroticism is so individualized, and has been so mass-marketed—in independent arthouse films, in mainstream media and advertising, in the push to produce an ever-more-provocative Palme D’Or winner at Cannes, and in the ever-present nearness of hi-def pornography—that it’s hard to define what constitutes, say, the “uniquely erotic” and who might be the audience or judge of that. That said, when I learned that the director of Oldboy—a film which earned him a great deal of well-deserved praise for the eye and imagination he brought to his work—has created another movie that was a highly acclaimed “erotic psychological thriller,” I thought I would check it out. I was disappointed. As with many horror movies that try to stand out from the standard Hollywood slasher, horror films that want to be smart, that want to be a film rather than just another movie, the best it seemed to be able to do was try to draw the viewer into a realization that they, themselves, may be like the villains in the film who are (in one way or another) getting-off on the violence or sexual objectification of others. This act of turning the film into a mirror in which the viewer finds their own reflection has been so overplayed at this point, that I’m not sure that anyone is going to see anything there that they have already seen before.

4. Cargo 200 (2007) directed by Aleksei Balabanov.

So then, after a few disappointments, I thought I would check-out the equally high-praised Russian film film noir, Cargo 200. I’ve always been something of a Russophile when it comes to literature and film and I thought it would be interesting to watch something that was also taken to be a political commentary on Russia’s war in Afghanistan in the ‘80s. This was a mistake. I did not enjoy this movie and I do not recommend it. And, okay, I know, sometimes people feel like they must present the most shocking and horrific thing they can to try and communicate the shock and horror of real-life events. But, I don’t know, I felt like Balabanov was getting off on it. And I know that others will, too. No thank you.

Documentaries

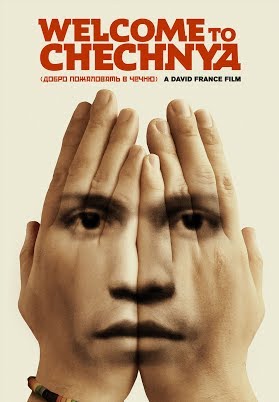

1. Welcome to Chechnya (2020) directed by David France.

In 2017, the Chechen police, judicial authorities, and members of the general public, began to engage in a campaign of incarceration, torture, and murder directed at anyone who was identified as Queer. It is unknown as to how many people were disappeared or killed but more than 100 were incarcerated and tortured. Extra judicial killings (and other acts of violence) were also recorded with cell phones and the videos posted online (to general approval from others). Anti-Queer violence continues to break-out in Chechnya with at least 40 people “detained” and at least 2 killed in 2019. David France manages to document some of this, while focusing on a small group of Queer activists who run a safehouse at an undisclosed location in Russia and who try (not always successfully) to aid Queer folx in fleeing Chechnya and seeking asylum in other countries (31 of whom were relocated to Canadian-occupied territories with the support of Toronto’s Rainbow Railroad). It’s a sad and inspiring and horrifying documentary which, I think, should be watched lest se forget that safer spaces for Queer people came through great struggle and must be continually defended and expanded or else they may well be taken away.

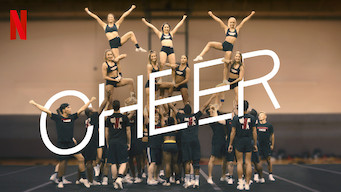

2. Cheer (2020) created by Greg Whiteley.

A Netflix docuseries, I initially sat down to watch this so that I could gap-out to some high-quality reality TV after a hard day’s work. I became absorbed. I fell in love with the human struggles of the team members, and by the end I was on the edge of my seat and then jumping up and down cheering out loud for them. There is so much that is good about this series. Recommended viewing.

3. The Painter and the Thief (2020) directed by Benjamin Ree.

Some of the greatest documentaries are created by directors who ,through no fault of their own, manage to stumble onto something absolutely rare and wonderful and unexpected, and manage to document that without fucking it up. Think The Imposter or The Wolfpack. The Painter and the Thief is something like that—with Benjamin Ree happening to be so situated as to be able to document a friendship that forms between a painter and the thief who stole her two most valuable paintings from a gallery when he was on a three-or-four-day bender. But Ree manages to take things one step further—he manages to frame things in such a way as to actually improve upon his remarkable discovery. Thus, not only to we see the thief from the perspective of the painter (that would be the rare and wonderful and unexpected discovery as, for example, the shot of the thief when he views the portrait the painter painted of him, makes the whole film worthwhile), we also see the painter from the perspective of the thief and the whole thing is so humanizing and equalizing and fuck, yeah, life is equal parts fucked and wonderful in all kinds of mixed-up ever-tragic and glorious and frustrating ways, and I can see why this was constantly rated as one of the very best documentaries of 2020. Highly recommended.