[I recently completed Miriam Toew’s latest book, A Truce That Is Not Peace (2025). I found it deeply moving. It prompted me to write the following reflection and I deliberately wrote it in a way that harmonizes with the voice Toews deploys in the book. Be warned: suicide is a prominent theme in what follows. I did consult with my brother prior to sharing this publicly and am doing so with his permission.]

Wittgenstein famously concluded his Tractatus by saying: Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muß man schweigen [Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must remain silent].” But poets and novelists have a different idea of what is speakable, what is not, and what other ways we might have of drawing closer to the unspeakable with words.

Then, later in life, Wittgenstein offered this corrective to his younger self: for heaven’s sake, don’t be afraid of talking nonsense. But you must pay attention to your nonsense.

Miriam Toews is a writer who pays close attention to her nonsense.

On, then, with the nonsense. For heaven’s sake.

~

The suicide of Toews’ father is a prominent theme in the novel. My father also came very close to suicide. After my mother escaped from thirty-three years of neglect and abuse, my father broke down.

Granted, as Darian Leader shows us, there are many ways of “being mad” that support people to function and succeed within the expectations and norms of our society. Leader refers to this as “quiet madness”—a well-developed but ultimately delusional system that a person deploys in order to live at “relative peace” in the world. The relativity of the peace produced by this “quiet madness” is important. The patriarchal violence of homonormative domestic arrangements is, for many men, a form of “quiet madness” (after all, our patriarchal society encourages this way of being mad). Thus, the result is peace for the patriarch and instability, terror, bodily harm, and constant anxiety for his family. When this arrangement is disrupted, when the person being harmed flees, then the system no longer works for the patriarch. Often, then, he transitions from “being mad” to “going mad.” This is when he becomes a greater risk to others and himself. The way-of-being in the world that enabled him to be at “relative peace” in society has collapsed. He might kill—himself or others—to get that back.

When my father was “going mad,” he was in London and I was in Vancouver. But, perhaps because of our emotional and spatial distance, he began to view me as a confidante. He called me. He emailed me. Quite a lot. I was already well-versed in the signs to monitor, the different “red flags” which signaled heightened degrees of risk, and I had already learned the art of having direct but caring conversations in order to determine when more immediate or forceful interventions might be required in relation to expressions of suicidality. Further, while I believed that every person has the right to choose to end their own life, I also believed that a person should be more or less lucid when making that choice (although, of course, mental health professionals will say that a person who wants to die and tries very hard to do so is, by that very fact, deeply mentally unwell… but, as we shall see, I’m not so sure about that).

Even before I was a social worker, when I was homeless as a teen, I remember doing much to support friends (also impoverished, also homeless) who wanted to die. I remember sleeping on the floor in one friend’s bedroom, in front of his door to help keep him safe at night. This is not a great strategy—it’s just what kids do when they care about each other. And, really, one thing that I’ve learned is that, while a few key environmental, contextual, and structural elements can, at times, play crucial roles, the more important thing is showing up with love in whatever way you can, for however long is necessary. It’s important to show people that you care about them and also that you love the love they have shown you. The second part of that is just as important as the first—because one of the most insidious lies suicide tells us is that our love is not good (h/t to Johanna Hedva for that phrase).

I was never closer to killing myself, personally, as I was sixteen years ago when I truly began to believe that my son would be better off without me. I remember sitting on the iron girders of the Cambie Bridge in Vancouver. I was thirty or so stories in the air with my wallet on the beam beside me so that they could identify my body. It was 3am and I was drunk and despairing and realizing that perpetually self-soothing with alcohol is just a way of prolonging one’s death. “I’ve gotta get busy living or get busy dying,” I thought to myself. And I thought about my newborn son, and I thought about studies demonstrating that children of parents who suicide are statistically more likely to suicide, and I got up and put my wallet back in my pocket and started the process of healing the parts of myself that felt like they needed to be drunk in order to find life bearable.

~

Ford Maddox Ford: I dare say, all this may sound romantic, but it is tiring, tiring, tiring to have been in the midst of it.

~

While I was in Vancouver, I worked at a shelter for youth who had been abandoned by their parents, caregivers, and the child welfare system. I still vividly remember the first teen I knew who tried very hard to die but didn’t (he simultaneously drank bleach and deeply slashed his wrists in the “proper way,” although I suppose it’s sort of nonsensical to describe it that way). Surviving was very painful for him. I also vividly remember the first youth I knew who really wanted to die and did. Due to the severity of his suicidal ideation, he had been moved from the youth shelter to an in-patient psychiatric ward but the doctors believed he was improving and so they granted him a day pass (just like Toews’ sister on the day she died). He went to his friend’s house, sat down on the bathroom floor, and hung himself from the door handle with his belt. All he had to do to stop dying was stand up. But he didn’t stand up. I still think about this young, Indigenous man a lot. He was such a beautiful spirit. Such a tender heart. He was shy and oppressed, gentle and abused, innocent and thought it was all his fault.

~

~

My dad was not shy, gentle, innocent, or tender-hearted. He abused my mother and my brothers and made me homeless in the middle of winter. I remember carrying my few belongings over my shoulder in a garbage bag, walking down a street covered in sheets of ice. All the trees, every branch, every twig, coated and shining like crystal under the streetlights. I blamed myself at that time. I spent years thinking “I want to die… I wish I was dead… I should just kill myself…” until I realized that that voice in my head wasn’t my voice—it was the voice of my father and the other men with power who abused me, who colonized my subjectivity. It was they who wanted me to die. Me? I wanted to live, but with less suffering. So, I started speaking back to that voice. I said, “No, that’s not true, I don’t want to die. I want to live and be content. I want to live and be at peace. I want to live and rejoice.”

~

Nonetheless, when my father’s breakdown occurred, I tracked closely with what he was communicating. I felt that he deserved that kind of care, not because he was my father, but because he was a human being. So, when the time came, I called my oldest brother, the one who like Toews’ older sister, would also have a close relationship with suicide (due to his accumulation of childhood trauma, chronic pain and illness, and C-PTSD sustained while working as a Paramedic in Toronto). I said to him, “J, you’ve got to go to London and convince the old man to go to the hospital. I think it’s highly likely that he will kill himself in the next few days if we don’t intervene.” When my brother got to my dad’s house, my dad had sealed off his bedroom with shrink wrap, he had a charcoal barbecue in the bedroom with him, and he had letters to each of his children beside his bed.

~

Heather O’Neill: [He] was one of the worst breed of parents going, the ones who are really mean but then don’t even give you the satisfaction of being able to hate them. They just break your heart. They were able to do whatever they pleased and then still have you love them.

Jean Améry: A rustling and crackling and hissing. What was it they said? Be careful or you will burn, all ablaze. All a blaze. Let my unhappiness burn and be extinguished in the flames.

~

Since then, my dad has never, to my knowledge, tried to kill himself again, although it has been more than ten years since I last spoke with him.

He recovered well in the hospital. He met a lady there. Eventually, he got a day pass and he used it to go home to put on a suit and buy her an expensive gift.

I’ve known many people who have fallen truly, madly, deeply in love in the psych ward over the years. Those relationships seem to be as long-lasting as relationships that develop elsewhere.

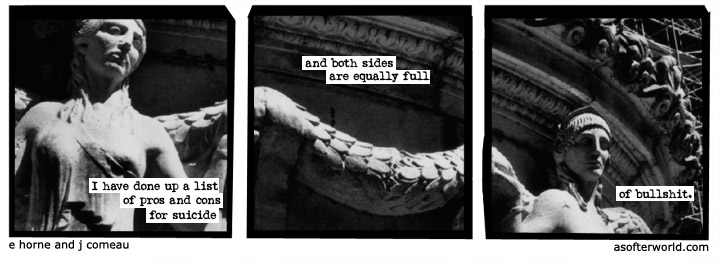

My brother, J, never went to the psych ward and he never completed suicide. He came very close a few times. Now, he finds comfort in the brevity and meaninglessness of life. If this is all bullshit, and it will all be over before we know it (“it lasts forever and then it’s over,” to quote another great book title), then why not live another day? That’s his take.

It was his suffering that first awakened me to the awareness that sometimes dying might really be better than living. I remember him writhing in pain in an emergency bed at the hospital after months of devastating pain and sleeplessness as he wasted away from being 6’1” and 200lbs to being 6’1” and 98lbs. His bowels were in the middle of rupturing in the ER, although the doctors didn’t realize that yet because they weren’t taking him seriously because he had been to the hospital so often and he didn’t like to complain. For the first time in my life, I prayed—because I still prayed then—for someone I loved immensely to die. “It’s too much, Jesus,” I said. “Jesus, take him home.” But Jesus didn’t take him home and the surgery was a relative success. But they released him from the hospital too soon post-op. I had to carry him back in because he had vomited and his incision had ruptured and I could look inside his abdomen and see his organs and our dad had found him on the bathroom floor and our dad had said, with a look of disgust on his face, “either go to your room or go to the hospital but you can’t just lie on the bathroom floor whining.” The incision eventually healed and he never really got that much better but he didn’t die and he didn’t kill himself and I think his children are glad that he is alive and so am I.

What a lot of nonsense.

~

Virginia Woolf: Dearest… You have given me the greatest possible happiness… I can’t fight any longer.

Anonymous (suicide note, apocryphal): All this buttoning and unbuttoning.

~

Nonsense, for Wittgenstein, means that which cannot be incorporated into a system of rigorous logic. By which he means that which cannot be pointed at, so as to say, “that is a that.” Wittgenstein loved tautologies. He wanted language to come down to saying “A = A.” Which is why, for him, truth was a product of language games played according to the rules assigned to them. This, for Wittgenstein, made sense. Everything else? Non-sense.

that’s a lot of non-sense! Some people find that distressing. Others, like my brother, J, find it liberating. Or, at least, “good enough.” As for me? Well, it makes me pay attention.

~

~

All of this leads directly to the core question motivating Toews’ book: “Why do I write?”

“The writing is the reason,” states Toews. “Bullshit,” her correspondent in Mexico City replies. “Precisely,” I say to both.

Bullshitting, according to Harry Frankfurt (what a name!) is not the same thing as lying. The bullshitter gives no thought to The TruthTM while trying to persuade their audience. The liar, on the other hand, cares very much about The TruthTM and wants to keep it hidden. As such, Frankfurt goes on to say, the bullshitter is actually more dangerous than the liar because the bullshitter undercuts the foundational importance, the very sacredness, of truth. Bullshitting breaks the fourth wall of the language game. But, if we extend our analysis of these language games forward to Foucault, we are compelled to ask, “who made the rules of these games and who benefits from all of us playing this way?” Knowledge ain’t power, says Foucault, it is power that determines what gets constituted as knowledge.

As for me, I have seen how the truth is continually weaponized against the already-oppressed in order to oppress them further: “Did you have any beers tonight?” the shelter worker asks the man checking in at the front desk. “Yes,” the man replies. “You broke the rules and can’t stay here,” says the shelter worker. The man is then sent to sleep outside, even if it is -40OC. I have known several people who have died this way. In such a death-dealing situation, I believe we all have a moral obligation to lie. Or, at least, bullshit as if someone’s life depended on it. Because it did and it does.

~

Wendell Berry: As soon as the generals and the politicos can predict the motions of your mind, lose it. Leave it as a sign to mark the false trail, the way you didn’t go. Be like the fox who makes more tracks than necessary, some in the wrong direction.

~

When I was younger, I was drawn to writers whose voices rang with apocalyptic realism. Writers like Cormac McCarthy and Margarita Karapanou hit me with their words and left me gasping for air. As I aged—as I healed from old heart-wounds while gaining new physical-wounds from years spent doing work human bodies shouldn’t do for very long—I became more drawn to what I have elsewhere described as the “apophatic realism” of writers like W. G. Sebald. Of course there are things that cannot be put into words. Not really. And, over and over again, it is precisely these things that drive the author, the poet, the artist, to create. Sebald writes about such things. But not directly. He walks long distances to circumnavigate them. He comes close to parts of them and then pulls back. He wanders away from them to see how they are experienced when they are not there. He writes of things in their proximity, things they have touched, and subtle changes that people carry inside of themselves because of these unspeakable things. He can’t quite get to the thing itself. And that’s the point; none of us can.

The indescribable is indescribable. Of course it is (A=A). But, for heaven’s sake, that doesn’t mean we should be afraid of describing it. However, it is wise to pay attention to how and why we go about doing all of that describing. What is lost and gained? For whom?

~

Toews: All silence is language… Writing isn’t talking. Writing is also non-talking.

And again: If silence says more, why write?

~

How, for example, could one possibly put a mountain range like the Cairngorms into words? Nan Shepherd and Robert MacFarlane certainly try. But they succeed not so much by what they say—as beautiful and reverent as it is—as by what they do not say, what they fail to say, what they cannot say. I cannot speak a mountain. I can never fully experience or know a mountain. I can glimpse its peak through the trees on a sunny day, I can see the aspen and alpine thistle on its eastern face from a distance, I can drink from the stream tumbling down it on a rainy day, I can even see it from above on Google Earth or place an image of it on a chart next to a picture of famous tall buildings in order to estimate its height—but this is nothing close to fully knowing, let alone fully experiencing a mountain. And if that’s the case for a single mountain, how much more is it the case for a mountain range? And if that’s the case for a mountain range, how much more is it the case for such nonsensical things as love and grief and care and wonder?

It has been said that the people of Nepal never summited many of the peaks that became famous alpine adventure destinations after the Europeans arrived. To the Nepalese, the mountains were sacred. Their beauty was to be adored with one’s eyes, not walked upon with one’s feet. It was only after the arrival of European men that beautiful places were up for grabs. “Mount Everest?” I can imagine Edmund Hillary saying, “I moved on her like a bitch… I didn’t even wait… I grabbed her by the pussy.”

~

Nan Shepherd: often the mountain gives itself most completely when I have no destination, when I reach nowhere in particular, but have gone out merely to be with the mountain as one visits a friend with no intention but to be with him.

~

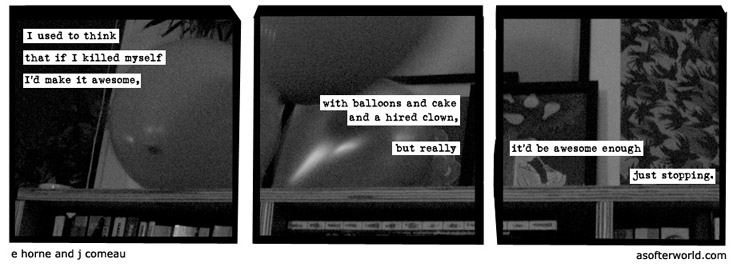

I have never spoken this part aloud but one of my longest-running fantasies is that, if or when I am finally overwhelmed by all of the everything, I will completely cease talking. I will lie down on the ground, wherever I happen to be, and I won’t move anymore and I won’t talk anymore and I will just stop.

Toews’ mother said that Toews’ dad and sister went for long periods of time without talking because it was their (penultimate?) effort to feel like they had some kind of control. Toews seems unconvinced by such an obvious explanation (although smart people often mistake “the obvious” for “the stupid” and then avoid it, even when doing the stupidly obvious thing is precisely what they need to do—cf., for example, the life and death-by-suicide of David Foster Wallace).

~

Pink Floyd: I think I should speak now (Why won’t you talk to me?)/ I can’t seem to speak now (You never talk to me)/ My words won’t come out right (What are you thinking?)/ I feel like I’m drowning (What are you feeling?) I’m feeling weak now (Why won’t you talk to me?)/ But I can’t show my weakness (You never talk to me)/ I sometimes wonder (What are you thinking?)/ Where do we go from here?

~

Why do mountains mountain? The mountaining is the reason.

Why do I write? The writing is the reason.

According to Christopher Bollas, we all “desire to elaborate the idiom of [our] being.” To be is to develop one’s particular idiom and to be able to develop well, in a way that allows one to persist without becoming chronically ill or stunted (in one’s core) through the various changes that occur in life, one must learn to inhabit one’s own idiom. For Bollas, this idiom is the core self. He describes it as follows:

Each self is born with an as yet unrealised idiom… If a self is comparatively free to establish its own idiom of being and relation through environmental provisions, then it will instantiate an idiosyncratic aesthetic, as it shapes and forms its world in a manner peculiar to itself. So each self will find particular individuals more attractive than others, will find certain actual objects… of more interest than others, and in the course of living a life will have constructed a world which, although holding objects in common with other selves, will have shaped them into a form as unique as their fingerprint.

Writers, then, do their idiomatic being-as-becoming before the eyes of others. It is their way of realizing their idiom of being. They write because, like all of us, they are elaborating, exploring, playing with, and discovering their core selves. As such, writers engage us and invite us, as we are able, to learn to speak and be our own selves.

The writing is the reason just as the mountaining is the reason. Just as all things when they are mostly left unharmed—in ecosystems that naturally incline towards mutual benefit, fostering the ever-expanding diversity of life—burst forth in a spontaneous way of being that is good. Why are the apple blossoms blossoming? The blossoming is the reason. Why is the winter wind howling? The howling is the reason. Why is the stone sparkling in the river? The sparkling is the reason.

At least for a little while. Which is all we have.

~

The Philokalia: Abbot Lot came to Abbot Joseph and said: “Father, to the limit of my ability, I have kept my little rule, my little fast, my prayer, meditation and contemplative silence; and to the limit of my ability, I work to cleanse my heart of thoughts, what more should I do?” The elder rose up in reply, and stretched out his hands to heaven, and his fingers became like ten lamps of fire. He said, “Why not be utterly changed into fire?”

~

The living is the reason.

The dying is, too.

Beyond that, none of us can say.