PART 1

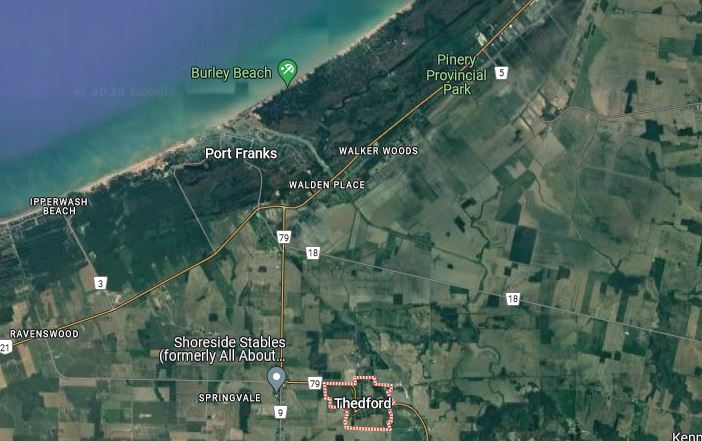

In 1955, wealthy White settlers drained the final remnants of the Thedford Bog. The bog’s rich black soil was considered some of the best agricultural land in southwestern Ontario. Three marshy lakes—Lake Smith, Lake George, and Lake Burwell, separated from Lake Huron by large sand dunes (dunes that are also on the verge of being completely gone)—were simply disappeared. They went missing. They were murdered. Lake Smith alone spanned 200-400 acres of open water with 600-800 acres of floating bog surrounding it. In 1937, The Canada Company sold most of that lake to Dr. Gordon Hagmeier. Initially used for duck and game hunting, he spitefully decided to drain the whole area when the Department of Lands and Forests fined him for hunting out of season (so it goes when land is converted into “private property” and made into a “resource” than can be hoarded by the rich). Thus, by 1955, the wetlands were gone and, much like the vast expanses of Carolinian forests that were logged across the region, the settlers exploited the richness of the soil—soil that had once been an integral part of thriving ecosystems—in order to expand Canada’s production of tobacco, winter wheat, and corn feed.

For thousands of years, the Thedford Bog served as a stopping point for millions of Tundra Swans. Tens of thousands of swans would stop at the bog on their spring migration from Chesapeake Bay in Delaware to the artic coast (an annual round-trip of 12,000kms). In the bog, the swans found safety, sustenance, rest, and, I reckon, the joy that accompanies finding such things while engaging in a long and arduous journey. A home away from home or, perhaps, one of many homes the swans inhabited during lives that were tuned to the cycles of the seasons, the span of time given to them, and the gift of flight.

Today, Tundra Swans still stop on the farmers’ fields in Thedford (70kms west-northwest of my home in London, Ontario). No longer traveling in the tens of thousands, when locals go to “see the swans” they are fortunate to see a few hundred birds picking at whatever remnants of genetically-modified farm feed were left on the scarred and frozen furrows of earth where the birds have landed.

Generations have come and gone since the bog was drained (the average lifespan of a Tundra Swan is ten years), but the swans continue to stop here. After thousands of years of nature and nurture—epigenetics and teaching younglings where to go—the swans do what they have always done even though the safety, sustenance and perhaps even the joy and feeling of being-at-home, are gone. So much has been taken and so many have come and gone since the taking, that I imagine that even the awareness of what was taken is gone. I can’t imagine that the swans remember why they used to stop here. I imagine they know that they are tired from their long flight. I imagine that they want to rest their weary wings awhile. I imagine that they stop where they have always stopped before. I imagine they imagine that this devastated land—land that barely supports the few hundred who land there now—was always this way. It’s not much, but, hey, one has to stop somewhere so it might as well be here. It’s not like there’s much of much left anywhere else.

This spring when the Tundra Swans passed through, locals like me pulled over at the side of the road and said, “wow, look at all the swans.” And we gave thanks for the beauty we witnessed in the hundreds and we were grateful to be alive and here to share in all of this annihilated everything with all of those we have annihilated.

PART 2

I was born in London, Ontario. I was abused as a child in London, Ontario. I was abandoned as a teenager in London, Ontario. I was homeless as a teenager in London, Ontario. I left London, Ontario, and swore I would never return. Over the years, when I occasionally returned to visit loved ones and my parents, I was struck by the ways in which London was such an obvious stronghold of White supremacy, heteronormativity, homo- and trans-antagonism, Evangelical Christianity, hopelessness, and creeping devastation. After every visit I reaffirmed to myself, “fuck, I’m so glad I got out of there,” and also, “I’m never going back again.”

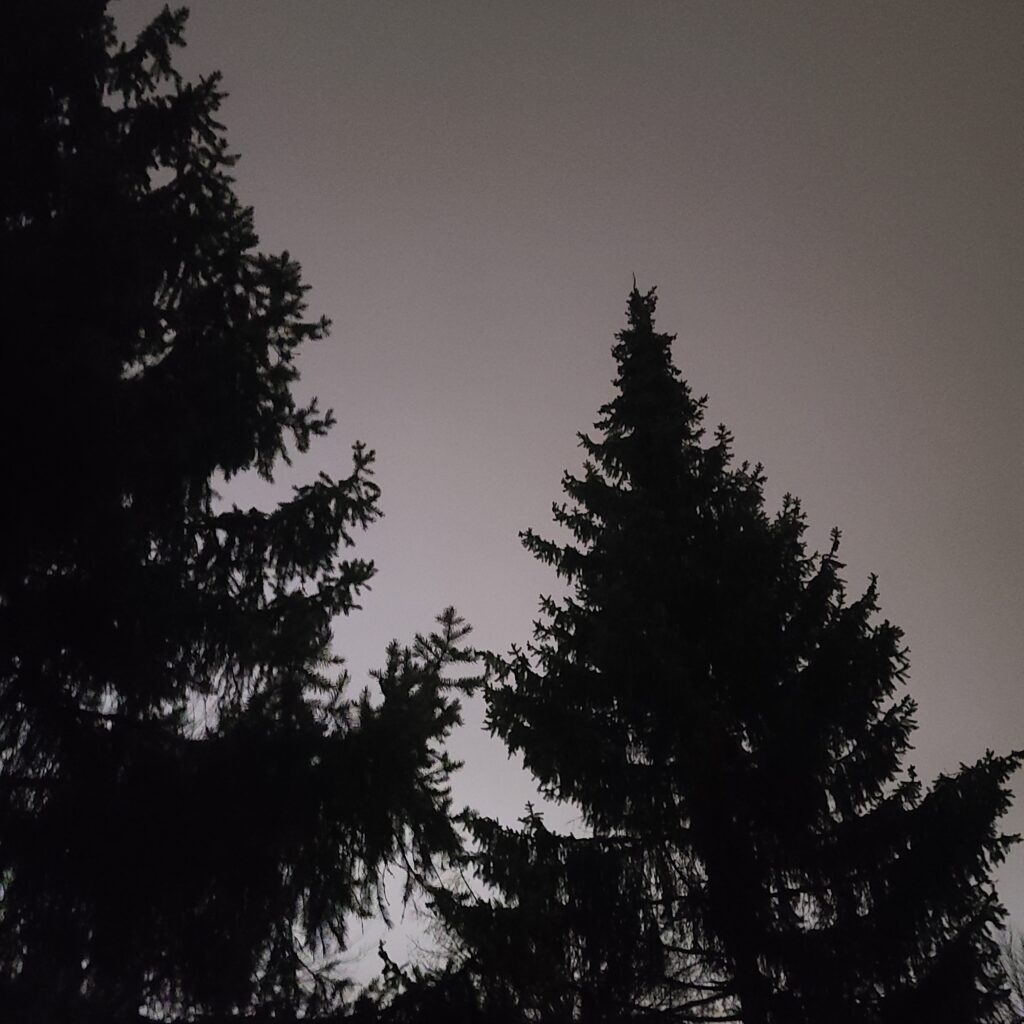

I moved back to London, Ontario, in 2013. Since my return, I find myself being pulled back to the places I used to inhabit as a child. Places where I used to find sustenance, rest and, yes, some joy, but also places where I fled for safety, where I sought respite, and where I tried to find shelter. The swings I sat on all night when I had no place to go. The 24-hours Tim Horton’s where I would try to sleep before they kicked me out for sleeping. The high-school I attended. The mall where we skipped class to play hackey sack. The field behind the church I attended where I tried to sleep on Saturday nights. Most of these places are still there. Some are modified. The climbers in the suburban park where I slept most are gone and have been replaced with safer climbers at a slightly different location in the park. The swings are still in the same location but have been replaced with a different swing set and woodchips have been added. The three very sappy spruce trees are still next to the swings and, when I hugged them again all these years later, were still very sappy.

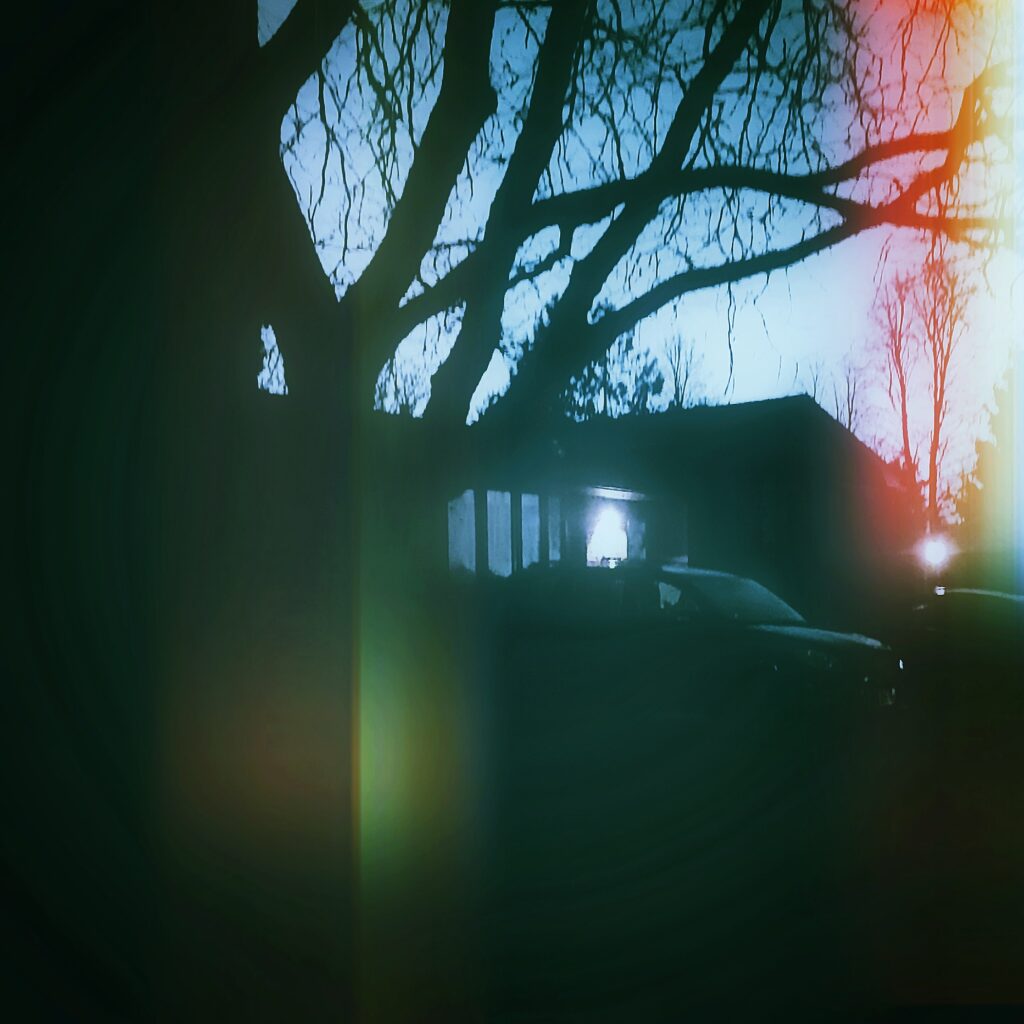

But no place calls me more than the house where I spent the first seventeen years of my life. I have only driven by it a handful of times since 2013, but I feel it calling me in a way that I imagine is comparable to the ways in which the former Thedford Bog still calls to the Tundra Swans. A few weeks ago, when I was doing some thinking about parenting, belonging, home, and connection, I decided to take an evening stroll through that old neighbourhood. Down the streets I walked and biked as a child. Back behind the variety store where I would go for penny candies. Into the park where I slept as a teen. Some memories came back to me—memories of a field that used to be where a massive suburb now exists, memories of hopping a friend’s back fence to go catch tadpoles, memories of who lived in every single house on the street, memories of riding bikes with neighbours down walking paths between houses. Some memories came in an instant, some took shape and I could hold onto them, others flashed by and were gone again before I could put them into words. The contours of the earth under my feet felt familiar to my body, even though I knew the ground must have changed in the last twenty-six years. Still, I recognized the way the earth dipped and rolled in the wooded area behind a church, I remembered vanishing into worlds of my imagination exactly there, between those trees, where the earth permitted hiding.

In the midst of all this remembering, the house where I grew up gave me… nothing. I walked by it, and it was like a great blankness at the centre of everywhere else where memories were proliferating. I felt nothing, saw nothing, and heard nothing. What I remembered was still what I remembered. What I didn’t remember was still everything else.

I am like the Tundra Swans. I go back to the house where I grew up seeking parts of myself that were taken from me but they are not there. No vestige of them remains. And the memories of those parts have been eviscerated along with them. Like the swans, I pass by and through not knowing why, not finding what was there at one time long ago. I am not even aware of what used to be there or why I might still go there now. What was lost will not be found. What was taken will not be returned. What was devastated will not be restored. All I can do, on my migration home, is stop and rest my weary feet awhile.

A beautiful read, Dan.xxx

A beautiful read, Dan.xxx

Thank you, Jackie! I appreciate little notes like these.