Discussed in this post: 6 books (Acts of Resistance; Rent; State of Insecurity; Rentier Capitalism; On the Golden Porch; and American Innovations); 4 movies (Crimes of the Future; The Banshees of Inisherin; Speak No Evil; and First Cow); and 2 documentaries (Phoenix Rising; and Harvard Beats Yale 29-29).

Books

1. Bourdieu, Pierre. Acts of Resistance: Against the Tyranny of the Market (1998).

A series of short articles and speeches delivered by Bourdieu in the mid-to-late-nineties, there’s nothing particularly earthshaking here. The most impressive things is how much Bourdieu anticipates features that will come to the fore in neoliberal austerity after the 2008 crisis (and up until the present day). He is quite prescient in the themes he chooses to emphasize and, while this would have been pretty critical commentary in the ‘90s, by now all of the core elements highlighted by Bourdieu have been much more fully developed by others.

There is no doubt that the theme of rent is one that has come increasingly to the fore in economic analyses of our present time. But rent, as Joe Collins explains, is a bit of an amorphous and contradictory thing, according to the experts who, it seems, have a lot of trouble agreeing with one another. So what do people say rent is and how did these various definitions, schools of thought, and arguments come to be? This is the focus of Collins’s book. It’s a bit technical and a bit basic (sort of like an ECON101 text, perhaps?) but, if you want to understand the the nuances between things like differential ground rent types 1 and 2, absolute ground rent, quais-rent, monopoly rent, heterodox rent theory, rent seeking, the differences between rent and profits, and why rent might be bad for capitalism qua capitalism, then this book will spell it all out for you.

3. Lorey, Isabell. State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious (2015 [2012]).

Isabell Lorey looks at how the biological state of precariousness (i.e. that we are mortal creatures with various vulnerabilities) is transformed into a political construction of precarity, wherein some people are sheltered from their biological precariousness, while other people are thrust into heightened states of precariousness or altogether given over to death and dying. It’s a good illustration of Foucault’s notion of biopower and how it creates and governs subjects. However, Lorey is particularly interest in how this precarity is constructed after the 2008 Global Economic Crisis—and she is particularly interesting when she talks about how our shared precariousness or different experiences of precarity, rather than being viewed in a solely negative way, can provide new foundations for solidarity, resistance, and liberation. In this regard, I found her chapter on “Precarias a la deriva,” a feminist women’s group of militant researchers in Madrid to be especially inspiring. All in all, a good read.

4. Christophers, Brett. Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and Who Pays For It? (2022 [2020]).

Although much of the attention of 21st century capitalism (also known as neoliberalism, since it is understood as a return to a modified version of the classical liberalism that came before a brief Keynesian intervention in the mid-20th century) has been on “financialization” (especially as it pertain to the global economic crisis of 2008) Brett Christophers highlights how rentierization has really moved into the poll position of driving the economy. Rent, he explains, is “income derived from the ownership, possession or control of scarce assets under conditions of limited or no competition” and this applies, as he goes on to show, in a remarkable number of fields (finance, natural resources, intellectual property, platforms, contracts, infrastructure, and land). Thus, the massive profits of rent extraction are related with the ability to create monopoly profits and, taken together, the economy as a whole becomes structured around rents. Thus, as Christophers defines it, ““Rentier capitalism is an economic system not just dominated by rents and rentiers but, in a much more profound sense, substantially scaffolded by and organized around the assets that generate those rents and sustain those rentiers.” He then spends the next 400 pages working through this market by market. I found it useful to read through it, in order to try and understand what is going on with rentierization, but his focus was on the UK and so, really, it just left me with a lot of questions as to how this applies to my own context. Broadly, I’m sure it’s very similar. In detail, I’m sure it’s very different.

5. Tolstaya, Tatyana. On the Golden Porch (1989 [1987]).

Tatyana Tolstaya was one of the hot authors of the Soviet literary scene in Moscow in the 1980s. Her short stories offer us a glimpse into all the little desperations, rages, and pretentions that linger inside everyday people. What Darian Leader refers to as “quiet madness,” is on full display here. One could also refer to it as “mundane madness.” We’re all mad here. Not like the Cheshire cat or the Hatter. More like the gal who stays with the abusive man because she thinks she can save him. Or like the man who stays in an abusive job because he thinks his hard work will be rewarded.

6.Galchen, Rivka. American Innovations (2014).

In Rodney Asher’s documentary about people who experience night terrors that are often just as vivid or even more vivid than waking-life (The Nightmare [2015], by far his best work to date), there is a lot of talk about terrifying shadow people who come into dreams, as if from another reality—a perhaps more real reality than ours—and who make even the idea of falling asleep seem terrifying. Some of the people Asher interviews mention that shadow people seem to be contagious—leaping from the dreams of one dreamer to the dreams of their partner after the original dreamer tells their partner about the shadow people. I found myself thinking about this after finishing Rivka Galchen’s collection of short stories, American Innovations, because I was unsure if Galchen’s stories were haunted or if the reader was the one who ended up being haunted by them. But precisely what in them or about them is haunting is harder to say. Is it beauty? Is it loss? Is it how hard it can be to get to the point? Do we even know what’s the point? Or, alternatively, is it the oh-so-personal-and-deeply-intimate-insignificance of our day-to-day lives that haunts Galchen’s characters? Or Galchen? Or us? It is hard to lay hands on those who haunt. How can one take hold of shadow? It is far easier for the shadow to take hold of you. But in my dreams, when the shadow people first approached me after I watched The Nightmare (my partner at the time regularly had shadow people dreams), I turned into a giant white bear and scared them away. They tried again the next night and I did the same thing. And they never came back. And I’m not claiming I can make any sense of that. I’m not trying to make sense of anything. I’m just trying to describe what happened. Because things that make sense are more frequently a product of imaginative story-telling and much less frequently a product of reality. And, anyway, this is what I thought after finishing Galchen’s truly excellent collection of stories. Highly recommended reading.

Movies

1. Cronenberg, David. Crimes of the Future (2022).

Crimes of the Future is sufficiently creative, sufficiently vague, sufficiently full of body horror that feels more like kink than the French variant—in other words, sufficiently Cronenbergian—that it could, no doubt, inspire a lot of clever commentary. There’s dystopianism, heady discussions of art, a noir edge, a mythical mother murdering her mythical child, pollution, and devastation and accelerated evolution (to say nothing of flesh-and-bone machines) that may or may not be salvific and yet… and yet it all falls rather flat. Honestly, it felt like Cronenberg’s remake of Star Wars Episode I, with a hooded-masked-and-cloaked Viggo Mortenson in the role of Liam Neeson, Kristen Stewart, the awkwardly comedic sidekick as Jar Jar Binks, and the dead boy, Brecken is the child Anakin. Both Cronenberg and Lucas looking for salvation. The latter failing to find it (for himself at least, even if it comes all too easily in his films), and the former concluding that, perhaps, it is little more than performance art.

2. Mcdonagh, Martin. The Banshees of Inisherin (2022).

The Banshees of Inisherin showed up on basically every list of “best movies of 2022.” But it’s a comedy… and it’s really Irish… so I skipped watching it until two close friends convinced me to see it. I’m glad they did. It’s an exceptional blend of humour and heartache, the deeply personal and the big picture political, the tender and the absurd. Is it a rom com? I wouldn’t say it isn’t! Is it a political commentary on the Irish civil war? Yeppers! Is it a profound meditation on human loneliness, love, frailty, kindness, and cruelty? Most certainly! Should you watch it? Absolutey!

3. Tafdrup, Christian. Speak No Evil (2022).

During the local Black Lives Matter protests—if you can call them that, since they were so pro-cop and bougie—I taught my kids the importance of saying “fuck the police” in the presence of the police. If we don’t learn to speak back to abusive authorities, if we don’t practice saying no and standing up for ourselves in small things, then when it comes time to say no and stand up for ourselves in big things, we may find ourselves frozen with fear or otherwise unable to do so. I know that my own childhood, wherein I was violently trained to be perfectly obedient, made it extremely hard for me to learn how to say know and set boundaries with abusive people once I became an adult. And so I often encourage children and others to practice small acts of rebellion, small acts of disobedience, so that when the time comes and it is absolutely essential to rebel, disobey, say no, bash back, whatever, they find themselves better prepared to do so.

I was thinking about this while watching Christian Tafdrup’s increasingly horrific, Speak No Evil, because it is about what happens to a couple and their child, who are targeted by another couple because they struggle so much to say no. Abusers, exploiters, bosses, rapists—all of these people learn how to pick out people whose fear response is not fight or flight but freeze, fawn, or fuck. And so, as the Danish couple alternate between freezing and fawning (with a few aborted flight efforts thrown in), they are slowly drawn further into situations that are uncomfortable, unsafe, and, ultimately, unalterable. This movie is far from being what people think horror movies are—it’s well shot, well directed, well acted, well paced, all of those things—but it’s not for the faint of heart. I thought it was great but you may not want to watch it.

4. Reichardt, Kelly. First Cow (2019).

Tales of the Old West tend to be filled with violence and violent men. Often this violence is glorified as a part of the great triumph of America and American men (think John Wayne—the actor, not John Wayne Gacy or John Wayne Bobbit… although each, in their own way, also provides us with a model of American masculinity). Or it is simultaneously etherealized and made into the very ontological bones of the world in an apocalyptic manner (see Cormac McCarthy’s work). Or it is presented as tragic and devastating acts of genocide (which it was). Nonetheless, when it comes to the Old West, violence abounds. But this is not the case in Kelly Reichardt’s film, First Cow. Reichardt helps us to remember the gentleness that exists in men. She reminds us of the beauty of the world and of the ways in which stories suffuse our everyday activities if we have just enough curiosity or wonder to look for them. Yes, many men are brutes and they create a brutal world and, yes, it’s hard for anyone not to get caught up in the ideologies of brutal worlds, but there is so much to life than brutality. There is, as Reichardt so powerfully shows us, friendship. There are all the little tendernesses that friends show each other. There is love and care that is shown simply because it is good to have a friend and delightful to love and care for them. In the end, I almost cried with gratitude for this reminder.

Documentaries

1. Berg, Amy. Phoenix Rising (2022).

I distrust Amy Berg. In two of her previous documentaries, she frames things in such a way as to maximize the shock and horror her viewers experience without any thought as to if this betrays her subject matter or harms the viewers. Thus, in West of Memphis (2012), she seemed to delight in repeatedly exposing the viewers to superfluous footage of dead children and in Prophet’s Prey (2015), she provides no warning to the viewer and exposes them to an audio recording of a man saying soothing things to a child he is raping (by the time you realize what you’re hearing, you’ve heard it). She does this again in the first part of her otherwise very good docuseries about Evan Rachel Wood, her activist work against rape culture in California, and the abuse she experienced from Brian Warner (Marilyn Manson). It really too bad because Wood’s work is important and stories like these are essential for exposing how deeply rooted rape culture is in all scenes—even those scenes that claim to disavow the mainstream toxic masculinity of jocks or businessmen. But, be warned: in the first episode Berg plays scenes from a music video and only gradually reveals to the viewer that Wood was raped by Warner during the filming of that video. In other words, the viewer is made to watch a literal rape and only told at the conclusion of the scene the full extent of what they watched. How a director making a film that targets rape culture can do this is absolutely beyond me. Fucking gross.

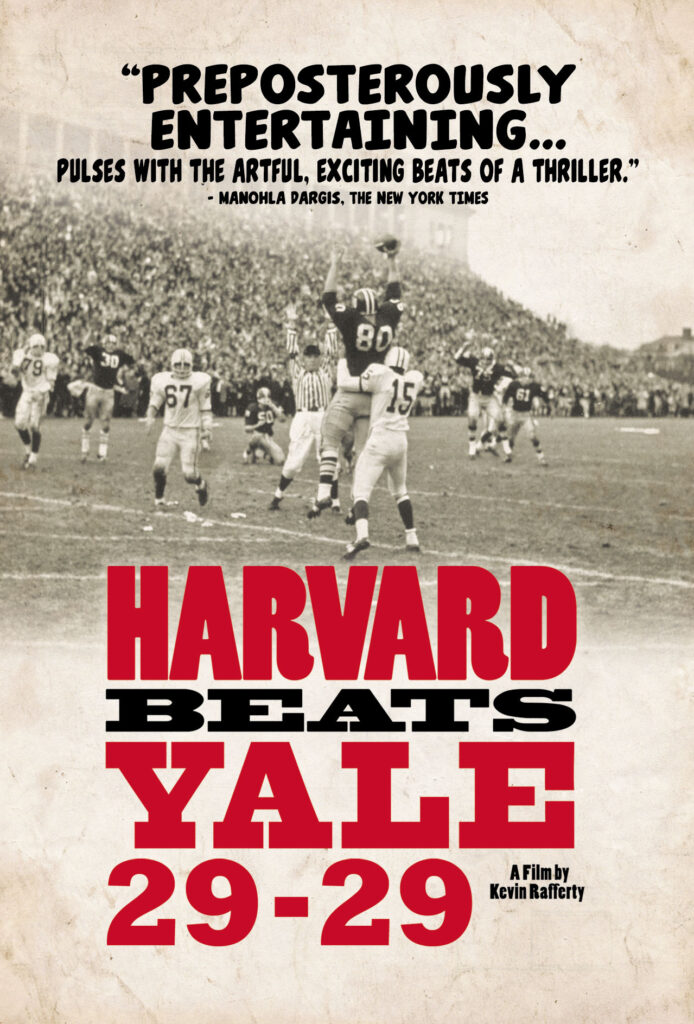

2. Rafferty, Kevin. Harvard Beats Yale 29-29 (2008).

In lists of “best documentaries” from the last twenty or so years, Kevin Rafferty’s Harvard Beats Yale 29-29 is regularly mentioned. I’m not usually super duper into sports-related documentaries (although there are exceptions, Ezra Edelman’s six hour long ESPN documentary on O.J. Simpson [O.J.: Made in America (2016)] and the Bryan Fogel’s Icarus [2017] being notable exceptions), but I decided to check it out. It was… okay. If you like football, especially American Varsity football, I am sure you’ll love it. If not, well, I think it’s pretty highly overrated.